Vladyslav Yesypenko is a freelance journalist for the Krym.Realii project (Radio Liberty) and the ICTV TV channel, a former businessman from Kryvyi Rih. In March 2021, he was detained by russian special services in occupied Crimea, accused of “espionage” and alleged possession of explosives. According to human rights activists, he is a political prisoner, according to the verdict of a russian court, he is a “criminal.” Yesypenko spent four years and three months in colonies, where he was tortured with electric shocks and beaten, trying to extract a confession to something he did not do. Despite numerous international campaigns and calls for his release, he was released only after serving almost the entire term.

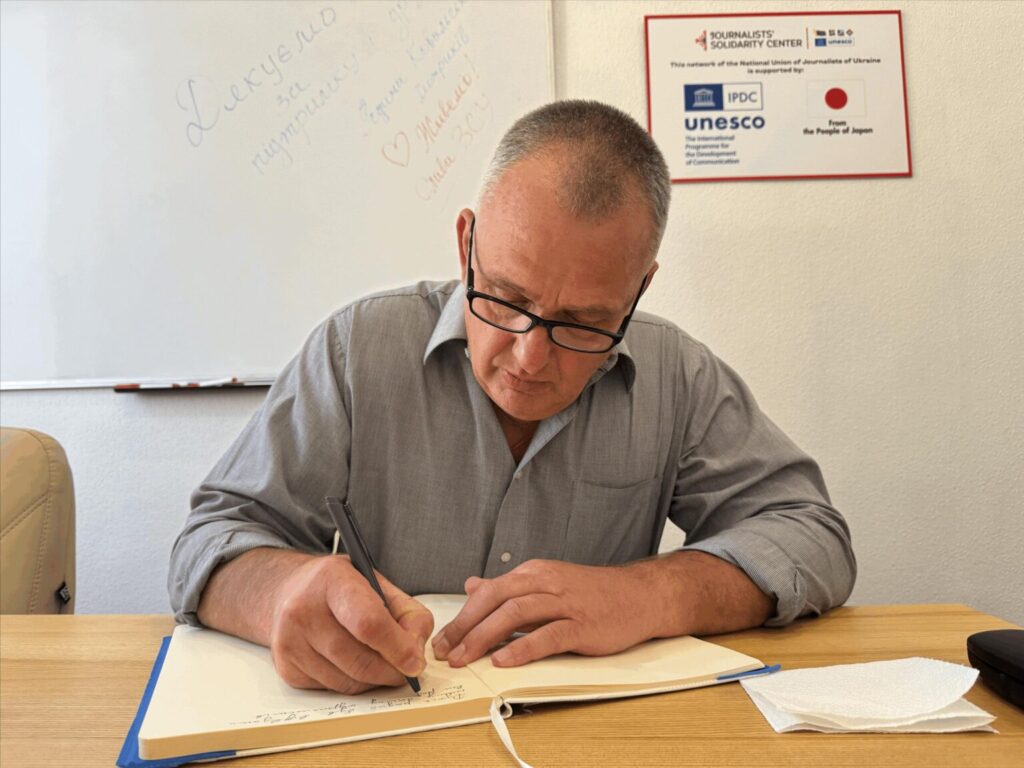

At the end of August, the journalist visited the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, where NUJU President Sergiy Tomilenko showed and spoke about the Journalists’ Solidarity Center (JSC), an exhibition of russian war crimes recorded by Ukrainian military correspondents, as well as solidarity with imprisoned colleagues, in particular Crimeans. He got acquainted with magazines and booklets published in support of legally imprisoned journalists and aimed at attracting the attention of the international community.

Vladyslav was most moved by a postcard with a drawing of his daughter Stefaniya – a symbol of indomitability and hope, created for the children’s illustration competition “I am from a family of journalists.”

We met with Vladyslav to record his testimony for a future documentary about imprisoned journalists, created in cooperation with the International Commission on Missing Persons. In the conversation, he mentioned torture, pressure, and attempts by the FSB to turn him into a “spy,” the support provided by letters from Ukraine, and the difficult adaptation after his release.

Today, he is gradually recovering and emphasizes that he plans to return to journalism and human rights. His main message is not to ignore those who are still in captivity: “it is important to return everyone — civilians, political prisoners, journalists.”

“Many international organizations appealed for your release, including One Free Press, Partners of the Platform for the Protection of Journalists at the Council of Europe, and Ukrainian parliamentarians. Petitions for your release were submitted to international institutions, such as the UN. Did this worsen the attitude of the russians, or, on the contrary, improve it?”

“In fact, it had almost no effect on my situation. The russians knew perfectly well that there was an international campaign, they knew about the statements of the UN, the Council of Europe, and various human rights organizations. But they didn’t care. Their main task was something else – to make me a “spy” to use in propaganda and discredit the Ukrainian media.”

The russians did not want to release me, not exchange me, but use me as a tool for their propaganda. They wanted to show: look, even journalists work for the special services.

Therefore, the support of the world was morally important, but it did not affect the attitude of the FSB or the prison guards. They did their job.

“What was the first contact with my family after the detention? Was there a possibility of correspondence?”

“I was allowed to make the first call only after torture and “investigative actions.” It was a very short contact, more for a check than for communication. Then they allowed correspondence, but it went through strict censorship. Some of the letters were simply not transmitted, others arrived with great delays.”

And when international inspections or monitoring groups arrived, I was specially hidden. Not because they were afraid to show the conditions, but because they were afraid: I might say something unnecessary, talk about torture, or the real treatment of political prisoners. That’s why they were taken out of the colony or locked up separately.

– In Ukraine, there are periodic actions called “Letters to a Free Crimea.” Did these letters reach you? What did you feel when you received them?

– Yes, I received letters. Not all of them, but enough to feel that I was remembered. It was truly support that helped me hold on. Imagine that you are sitting behind bars, isolated from the world, and suddenly you are handed a letter written by a child or a fellow journalist. It’s like a breath of air, a reminder that you are not alone.

I even received letters from people I didn’t know at all – ordinary Ukrainians and even some russians who did not support the war. It gave me strength.

“Our jokes were a weapon against the FSB.”

– I remember my first meeting with Nariman Celal in the colony. He got there later than me and already knew about my stay. When he recognized me, he came up to me and said a few warm words of support. This was very important because when you find yourself alone with the system, any friendly gesture holds huge meaning. From that moment on, we got stuck together.

We sat on different floors, but we managed to find a way to call each other. Sometimes it was as simple as a single word: “Friend, how are you?” – “I’m holding on.” Sometimes it was jokes. Sometimes we laughed at things that would seem absurd to an outsider, but that’s what saved us.

In prison, even humor becomes a form of resistance. If you can joke, they see: you haven’t been broken. This annoyed the administration, because it broke the expected “silent obedience.”

“Even simple movement there could be prohibited – everything was considered a potential escape attempt:” about conditions in the colony.

– I walked 10–15 kilometers per day in a very limited area — 40 meters there and 40 back. This was the only opportunity to move. For training, I used stairs and metal chairs, performing 5–10 approaches to maintain my physical fitness. It was difficult to do this due to limited nutrition.

The food was inferior. When the inspectors arrived, they laid white tablecloths and served more delicious food. After the commissioners left, everything returned to its usual state of shortage.

Medical care was almost non-existent. If someone had a chronic illness, it was necessary to obtain signatures from many people, including a general, in order to take them to a civilian hospital. We had a case when a young guy with diabetes was not given anything at night, and only in the morning was he transferred to the medical unit. And somewhere around 2 p.m., he died. This illustrates the extreme difficulty of the conditions: it was extremely challenging to survive both physically and psychologically.

– What helps you recover physically and psychologically after captivity?

– To be honest, adaptation is not easy. You return to a different world: different technologies, a different pace of life. In the colony, we were cut off from even simple things, like smartphones or the Internet. We had to learn all over again, from buying a ticket on the subway to communicating in instant messengers.

For Vladyslav, the experience in captivity altered his perception of home and family — now even the simplest moments with his family take on profound meaning. He feels a special gratitude for his loved ones, understanding that the true value of home is manifested in the support and security it provides.

– The first thing I did when I returned was to walk along the Dnieper River, feel the freedom, and see my loved ones

– Do you plan to continue your journalistic activities?

– Yes, definitely. It is a principle for me. I saw how the russians tried to use my case to discredit Ukrainian journalism, but I believe that right now we have to work even harder to show the truth.

– How will the experience of captivity affect your topics and approach to journalism?

– Now I know exactly how important it is to talk about prisoners. Because publicity saves lives. In colonies and remand prisons, we were hidden, but when they write about you, when there are letters of support, the correctional officers see that you have not disappeared.

That is why I want to work on topics related to prisoners, war crimes, and human rights.

My journalism will now focus on freedom — and those who still lack it.

“A special friendship is born within prison walls — the kind that saves when there is nothing else.”

Despite the fact that Vladyslav returned home at the end of June, he is already actively working to help other Ukrainians who are still in captivity.

– In prison, I met people who became important to me. One of them was Halyna Dovhopola. She was already elderly; at the time of our last meeting, she walked with crutches, but her strength of spirit was impressive. She did not give up; instead, she supported others, and in doing so, she set an example for herself. I realized that even in a colony, you can find a person who will help you survive. Unfortunately, some never returned; they were killed.

The main source of information for me now remains Facebook, where I talk about meetings with various people and human rights organizations, and also cover the cases of those who are still in prison.

– The support that prisoners receive through publicity, letters, and the media really saves lives. This is exactly what I have seen from my own experience. Therefore, my main message is not to ignore those who have not yet returned home. It is important to return to everyone – civilians, political prisoners, journalists.

Interviewed by Valeriya Parkhomenko

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post