Award-winning journalist Kateryna Lisunova, recognized by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU), has spent years challenging stereotypes about Ukraine in the heart of American power. She was the first Ukrainian journalist to receive resident correspondent accreditation status at the United Nations, reported live during the storming of the U.S. Capitol, and in September 2021, joined the Ukrainian Service of Voice of America as a congressional correspondent.

In a candid interview, Kateryna reveals surprising gaps in U.S. politicians’ understanding of Ukraine and shares a powerful message: “We need to remind American leaders — Ukraine isn’t fighting for territory, it’s fighting for its people.”

Lisunova speaks openly about how Russian propaganda seeps into American media, why even Ukraine’s closest allies are unaware of key developments, and what’s truly needed for Ukraine’s voice to be heard across the ocean.

“First of all, I want to sincerely thank the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU) for its outstanding and ongoing work in supporting journalists. In particular, I’m grateful for the Centers of Journalistic Solidarity, which provide a place for journalists to work—even under the most difficult wartime conditions, during blackouts, and amidst constant shelling. I honestly don’t know if anything like this exists anywhere else—in a country at war or anywhere at all. I truly hope these centers will continue operating, because the war is ongoing, and we’re seeing neither a decrease in the intensity of the shelling nor any relief in the challenges journalists face. If there’s any way I can support this important work, I would be honored to help.”

“It’s important for Ukrainian journalists to be the ones asking the questions”

Kateryna, you became the first Ukrainian resident correspondent at the United Nations. What does that mean, and how did you achieve it?

“Major media outlets have offices inside the UN press area — designated workspaces located within the headquarters. Having one of these offices or a personal work desk grants you resident correspondent status. It’s very difficult to obtain and there is a line. I was able to achieve it through a lot of hard work, persistence, and support of Ukraine’s Permanent Mission to the UN.

From my side, I made the case to UN representatives that issues related to Ukraine should be covered by Ukrainian journalists. For example, the UN Secretary-General’s spokesperson, Stéphane Dujarric, holds daily press briefings. When Ukraine comes up, it’s crucial that the questions come from Ukrainian journalists. Russian propagandists often phrase questions in ways that skew the narrative—and unfortunately, journalists from American or other media many times end up reporting the story from that angle.

But navigating the bureaucracy and making the argument wasn’t enough—I also had to prove my professionalism. Before receiving resident status, I worked at the UN without an office, producing a wide range of reports and stories. I submitted these as samples to the UN Press Office—specifically, the Media Accreditation and Liaison Unit (MALU), which oversees journalist access. At the time, I was working with “Pryamiy” TV and freelancing for “BBC Ukraine.” After reviewing my body of work, MALU approved my request and assigned me a desk relatively quickly — in about a year and a half.

Later, Ukrinform began covering the UN as well, and when I left my role, the workspace I had been using was transferred to them.

“Many of Ukraine’s supporters aren’t aware of some important developments”

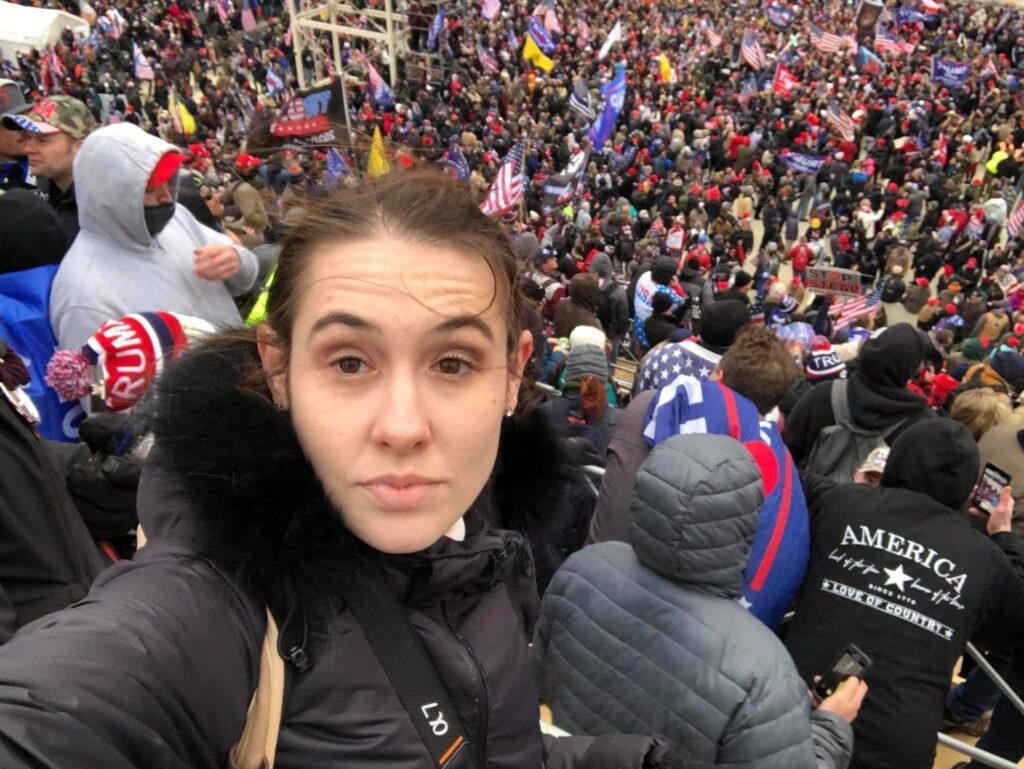

I know that on January 6, 2021, you covered the deadly riot in the U.S. Capitol, and just a few months later, you began interviewing leading American politicians. What does a journalist feel when they find themselves at the center of historic events?

“The storming of the Capitol was an unexpected event with many conflicting perspectives. Several of my American colleagues had their equipment destroyed. The people who stormed the Capitol wouldn’t let them report — and thank God they did not harm them. I had previously worked in Ukraine during the Maidan revolution, and I had covered many protests and riots, as well as looting in the U.S., so I had some idea of how to act.

Also, when I introduced myself as a Ukrainian journalist, the rioters responded more positively to me than to American reporters. I even managed to interview a few of them. I got their comments before the storm, during the rally near the White House. At first, people were saying they were peaceful and that nothing bad would happen. Later, I spoke to others who were already explaining why they had decided to attack the Capitol.

I wouldn’t call them ‘villains’ like in the movies. From what I saw, they were people who genuinely believed the election had been ‘stolen,’ and that they were ‘saving democracy, the U.S., the Constitution, and fair elections.’ Unfortunately, I think they were misled — fooled — but they clearly cared deeply about their country.

There was a moment that evening when almost no journalists were left near the Capitol. Law enforcement was pushing back the rioters, and I could hear smoke and stun grenades going off in the distance. I was filming a stand-up report on my phone, with a light on my face, making me easy to spot in the dark. I was nervous — I knew someone could approach me at any moment, and I didn’t know how they’d react.

After I wrapped up, several men — clearly participants in the storming — approached me. They were in tactical gear. They asked who I was, who I worked for, and then said, ‘Give us an interview. Tell us on video what you think about what happened today.’

I hesitated for a moment, but then I told them honestly: ‘I think you’re doing serious harm to your own country. Right now, only your enemies are celebrating.’ That may have been brave — or maybe reckless — but they listened. One of them said, ‘You’re probably right.’

I was relieved. But then I noticed: their hands were bloody. I said, ‘Your hands are bleeding?’ And they replied, ‘Yeah, we made a bit of noise back there…”

Based on your experience, how would you advise working with top global politicians—especially U.S. senators and members of Congress?

“There are a few key things. You need to be persistent and confident. They’re often in a rush, may not respond to emails, and usually don’t offer comments — but consistency and follow-through are essential to getting results.

I’ll say this: working for Voice of America really helped me cover U.S. events for a Ukrainian audience. American politicians on Capitol Hill typically don’t like giving interviews to foreign media. But since VOA is an American outlet, I was an American journalist, which made them more open to talking.

Interestingly, even some of Ukraine’s strongest supporters weren’t aware of major events that were widely reported in Ukraine and Europe. I often had to present background, quotes, and context just to get them up to speed before they could comment.

I have many such examples. One of the clearest was after Russia blew up the Kakhovka Dam. The Russians immediately put out a statement blaming Ukraine, and leading American media outlets reported that version — without waiting for a Ukrainian response. It took some time for Ukraine to verify everything and issue an official statement.

I remember interviewing Rep. Mike Waltz (R-FL), who was later appointed by President Donald Trump as a national security adviser. When I asked him about the dam, he told me it ‘didn’t make sense’ for Russia to destroy it, since it was on territory they already occupied. I pointed out that, by that logic, it didn’t make much sense for Russia to launch a full-scale war either — since it devastated their economy. That gave him pause.”

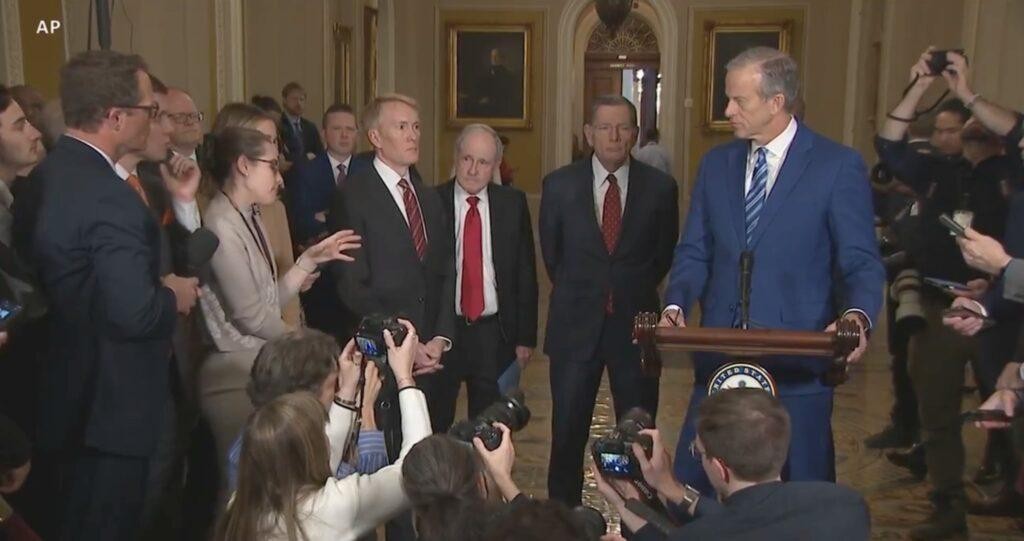

Which leading American politicians have you interviewed?

“Frankly, almost everyone in Congress. I had especially frequent interactions with House Speaker Mike Johnson. One of the most memorable moments was when he publicly supported Ukraine’s right to strike targets on Russian territory. In his words, “They (Biden administration) need to allow Ukraine to prosecute the war the way they see fit. They (Ukrainians) need to be able to fight back. And I think us trying to micromanage the effort there it’s not a good policy for the US.”

I conducted several interviews with Speaker Johnson. He came to recognize me as a journalist who consistently reports on Ukraine. There were times when he would avoid other questions from reporters, but still respond to mine — because mine were always focused on Ukraine. Local journalists often repeat each other or ask provocative questions, while mine were specific to one subject. I think that helped us build a respectful journalist–politician rapport.

Overall, I’ve probably interviewed nearly every member of Congress, from moderates in both parties to progressive Democrats and conservative Republicans. I had some particularly heated exchanges with hard-right Republicans like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz.

One of my last interviews was with J.D. Vance after he had become Vice President. I said, ‘It seems like currently there’s a lot of pressure on Ukraine from the U.S., but almost none on Russia. Does your administration plan to impose any new sanctions?’ At the time, he responded that many sanctions had already been put in place and that they believed they were applying pressure on both sides. But as you can see, things have shifted a bit, and now there’s more serious discussion about the possibility of new sanctions against Russia”.

Are there any fundamental differences between American members of Congress and Ukrainian people’s deputies?

“Yes, there are. With all due respect to Ukrainian people’s deputies, their roles often feel very temporary. Many enter Parliament based on shifting political trends. There’s a widespread perception in Ukraine that politics is a “dirty business”—a sentiment that likely stems from the trauma of the Soviet era. As a result, the Verkhovna Rada is often seen by the public as a place for dishonest people, which deeply undermines respect for the institution. Almost as soon as deputies take office, public trust and support begin to erode.

In contrast, members of the U.S. Congress are, in most cases, career politicians. These are individuals who have dedicated their entire lives to public service. Sometimes political involvement runs in the family for generations. It brings its own challenges, but at least many of them studied political science or law specifically to enter this field. They accumulate experience, deepen their expertise, and are able to explain complex processes clearly and confidently. You get the sense that these are people who are passionate about governance—people who will remain politically active even after they retire. It’s more of a calling than a temporary role. And because of that, they generally enjoy greater respect from the American public.

The electoral systems are also very different. In the U.S., each congressman or senator is elected directly by their local constituents—they individually campaign and fight for their seats. In Ukraine, on the other hand, there’s a party-list proportional representation system—sometimes referred to informally as a “quota system.” Voters choose a party, and then that party decides who actually enters Parliament. The result is often less direct accountability to individual voters.

Can you describe a typical day for a journalist covering Congress?

“A journalist’s day in Congress starts very early—almost at 5 a.m. You need to follow up on previous interview requests and send out new ones. You also have to catch up on events that happened overnight in Europe. Because of the time difference with Ukraine, international journalists need to stay constantly updated in order to tailor questions for members of Congress.

You also need to review the day’s schedule—and on Mondays, the agenda for the entire week—to see which committee hearings are related to Ukraine, whether any new Ukraine-related bills are being introduced, and whether any votes are expected that day. Then you check the scheduled press conferences and briefings, as well as the House Democratic Caucus and Republican Conference meetings, which are closed-door and typically held on Monday nights when Congress is in session. Just getting familiar with the full schedule is a job in itself.

By around 9 a.m., you’re already at the Capitol. I’m a multimedia journalist, so I didn’t have a separate cameraman—I carried my own camera, filmed interviews, asked questions, and arranged sit-downs with lawmakers. After gathering content, I’d edit everything—whether it was short sound bites, full interviews, or segments for larger stories. That included transcribing and producing the material. Then came live TV hits, studio segments, and writing articles. That’s what a day in Congress looked like for me.

And it’s like that the whole week. The busiest days are Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday—with Wednesday being the most intense. If you’re expecting an important statement about Ukraine—or really any major announcement—it will almost always come on a Wednesday.

I also want to highlight the incredibly supportive atmosphere among Congressional correspondents. Many American colleagues were generous and helpful. If I arrived a bit late to an event and something relevant to Ukraine had already been said, they would fill me in. Sometimes they’d even film it and send it to me. I’m incredibly grateful for that kind of solidarity.”

Which administration—Biden’s or Trump’s—is more open to journalists?

“It’s a bit of a paradox, and some of my journalist colleagues have pointed it out as well. For example, even though the Trump administration effectively shut down Voice of America, and the current administration often makes critical—even outright offensive—comments about the media, it’s actually far more accessible to journalists during public events.

Looking back at the Biden administration, President Biden rarely held live press conferences—you might hear from him once a month, if that. In contrast, the current administration—from President Donald Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance to others in their circle, even Elon Musk—engages with the press constantly.

They’re often highly critical of the media, calling it outdated or biased, but they never pass up a chance to talk to a journalist. To be honest, in some cases, they might actually be talking to the press a little too much.”

Photo Credit: Still from a the AP video

“Sometimes Americans will throw in a Russian word during conversation, thinking it’s a nice gesture—just to be friendly.”

Is the work of Ukrainian journalists reporting from the front lines of Russia’s war on Ukraine recognized in the U.S.?

“Unfortunately, the voices of Ukrainian journalists are still much quieter than those of major international media outlets. For that to change, Ukraine needs strong English- and Spanish-language media platforms. Ukraine arguably needs international journalism more than anyone right now.

For the voices of Ukrainian journalists to be heard across the ocean, they have to be powerful and loud—and that happens all too rarely. Sadly, I don’t yet see a consistent or systemic media presence. That’s one of the weaker areas of Ukrainian media right now. But where there’s a weakness, there’s also room for significant progress.”

You mentioned that during interviews with American politicians, you often have to explain events in Ukraine and fill in informational gaps. Are there any stereotypes or prejudices about Ukraine that you’ve had to overcome?

“Politicians who aren’t supportive of Ukraine often throw around phrases like ‘the most corrupt country in the world.’ But in reality, there’s no objective data to support that claim. Isolated, often unverified statements have evolved into political narratives—about misusing aid, or about the size of U.S. assistance being much larger than it actually is.

What many American politicians forget is that aid to Ukraine helps create jobs in the U.S. and strengthens America’s own defense industry. But these are political narratives, not necessarily stereotypes. And those narratives are often created or amplified by Russian propaganda, which pours massive resources into spreading them—and in many times, unfortunately, succeeds.

As for ordinary Americans, many still don’t fully grasp the difference between Ukraine and Russia. They may recognize them as two separate countries but don’t always understand that the cultures, languages, and national traditions are very different.

I’ve often heard well-meaning but misguided ‘sympathy’—remarks about ‘two nearly identical cultures fighting’ or about ‘families on both sides of the border divided by war.’ There’s little awareness that what’s often called a ‘shared history’ is actually a history of occupation for us.

Sometimes Americans will throw in a Russian word during conversation, thinking it’s a nice gesture—just to be friendly — without realizing that we don’t speak that language”.

How has coverage of Ukraine in American media changed since the war began?

“There’s definitely more understanding now. Instead of saying ‘Kiev,’ they’ve started using the correct spelling—‘Kyiv.’ They try to pronounce ‘Volodymyr Zelenskyy,’ not ‘Vladimir.’ There’s been a shift toward learning about Ukraine through Ukraine, rather than viewing it through the lens of other countries.

Until recently, as you may remember, many American media outlets had their regional headquarters in Moscow. From there, they would cover Ukraine—often without ever setting foot in the country itself. That approach is changing a bit.”

They say that coverage of Ukraine is fading due to the war’s long duration. Is that true?

“Once again, paradoxically, the current Trump administration has renewed interest in Ukraine and brought it back into the news cycle. Ukraine is being mentioned and discussed far more now than it was during the Biden administration.

That said, the reasons aren’t entirely positive—much of the attention stems from growing concerns that Kyiv could lose support from Washington. At the same time, successful Ukrainian special operations on Russian territory have also reignited conversation and drawn fresh attention to the region.”

Does American journalism differ greatly from Ukrainian journalism?

“It does differ. I’m not sure I’d say greatly, but there are differences. Sometimes, it even feels like there’s more freedom of speech in Ukraine—more opportunities for journalists, and in many ways, more rights.

At the same time, journalists in the U.S. operate under more rules—and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. For example, in Congress, if a senator or representative is on the move, you have to ask permission to walk alongside them and ask questions. If they agree, you’re good to go—if not, you can’t chase after them. In fact, running is strictly prohibited in Congress. In certain areas, even sitting is not allowed. You also have to follow a dress code—some parts of Congress won’t let you in if you’re wearing sneakers or casual clothes.

Another rule: you can’t use microphone windshields with your media outlet’s logo—no one is trying to brand themselves in the shot. These kinds of rules, in my opinion, actually help. They bring order and make the working environment more professional for everyone.

That said, there is a real problem with how the war is covered in American media. Too often, they place the aggressor and the victim on equal footing. They quote both sides as if it’s a legal dispute or a financial disagreement—completely ignoring the fact that you can’t justify rapists, killers, or psychopaths.

You cannot treat propaganda and misinformation as equal to the truth. When you quote both sides, at the very least, you should clearly state that all the previous claims of one of the sides have been proven false. Giving both sides a platform without context isn’t balanced journalism—it’s misleading.”

Voice of America has long been considered the gold standard for unbiased, objective journalism—going back generations, especially to Soviet times. But after the Trump administration’s decision to shut it down, has the Voice gone silent forever?

“Yes, Voice of America was vital during the Soviet era, and it remains especially important today for Ukrainians living in occupied territories. People wrote to me—particularly from occupied Luhansk—and to many of my colleagues from other occupied areas. For them, we were a voice of hope, a source of truthful information.

The very fact of such communication with people in occupied territories confirms that Ukraine is fighting not only for its self-preservation, not ‘for pieces of territory,’ but for people who remain in occupation, in terrible conditions. Attempts to liberate territories are attempts to free one’s people from occupation. This is a struggle for the life of every person who remains there.

Can we say that the Voice of America has fallen silent for good? I’ll say this: as of now it is silent. No broadcasts are happening, a court dispute is ongoing. How will it end? I can’t predict this, but we need to prepare for the fact that viewers, readers and listeners may not hear Voice of America in the near future.”

Photo Credit: Kateryna Lisunova

What does the invitation from PEN America to become a member mean to you?

“This invitation is part of a special PEN America fund established to support USAGM journalists. It offers short-term assistance to journalists and their families facing emergencies or at-risk situations following the March 14, 2025, Executive Order by Donald Trump, ‘Continuing the Reduction of the Federal Bureaucracy,’ which effectively defunded USAGM.

In essence, it helps Voice of America journalists who have found themselves in a difficult situation. I was offered support from this special fund, along with a complimentary membership. And I am very grateful for that.

In addition, PEN America has also agreed to help me create a photo exhibition showcasing the work of Voice of America. We are now working on this exhibition together with PEN and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. This is important because Voice of America was governmentally funded and, therefore, couldn’t promote or speak much about itself. Now, as the outlet is effectively being shut down after more than 80 years of broadcast, it’s important to tell our story. It may also help raise awareness and support for journalists who are now in extremely difficult circumstances.

PEN America, PEN International, and their regional branches do a great deal to support journalists. For example, they gave an award to Ukrainian journalist Vladyslav Yesypenko after he was illegally detained in occupied Crimea in 2021, which helped draw international attention to his case and demand his release. They also did this for Oleg Sentsov. I believe this kind of sustained attention can actually help free journalists and save lives. Thankfully, Oleg Sentsov was eventually freed, I hope the same will happen with Vladyslav Yesypenko.

PEN America also continues to shine a spotlight on the crimes Russia commits against journalists on Ukrainian territory. The organization speaks out clearly and consistently. Their language is factual and objective—occupied Crimea is called “occupied Crimea,” and the authorities detaining Ukrainian journalists are referred to as “Russian occupation forces.” That kind of clarity and precision helps draw international attention to the threats Ukrainian journalists face.

Beyond advocacy, PEN America also provides grants and funding opportunities for journalists. Ukrainian journalists who are proactive can take advantage of these resources and amplify their voices. Unfortunately, many don’t know these opportunities exist—so maybe this interview can help spread the word.”

What are your plans now, after Voice of America is closed?

“I can’t share too much just yet, but I do have plans. There’s certainly no shortage of work in journalism right now. If I’m able to continue covering Congress, that would be great—and I’m actively working toward that.

I’m also working on a book, and I’m involved in supporting women journalists and Ukrainian women in general through the Women’s Voice in Action organization, where I’ve recently become an ambassador. In short, there’s a lot to do.”

“The loudest voice can now, unfortunately, drown out all the others.”

You mentioned the importance of clear rules in journalism. When something new emerges, it takes time to develop those rules. In your opinion, how is artificial intelligence changing journalism, and do you use it yourself?

“I wouldn’t recommend that journalists—or anyone—rely too heavily on AI just yet, because it’s still very raw. Personally, I would never trust AI with important information, because I know it can often fabricate facts.

I do use AI to catch small mistakes in text. But the idea of AI replacing journalists is still a long way off. Right now, artificial intelligence is like a very young intern in a newsroom. If you’re using its help, you have to double-check everything, read closely, and keep tight control over every detail. That said, interns can be very helpful.”

What about social media networks? This is also a big challenge for journalism and information in general. What challenges do you face as an international journalist in the era of social media and disinformation?

“In today’s world, social media has become the biggest source of disinformation. What’s especially troubling is that the person who controls the narrative often isn’t the one with the facts—but the one who speaks the loudest and uses the simplest language. The loudest voice can now, unfortunately, drown out all the others.

That’s how narratives are created—through volume and repetition, not facts. And this connects to your earlier question about stereotypes of Ukraine. Many of those stereotypes are shaped by narratives that originate on social media and are actively pushed by Russian propaganda.

So, I’d say this: social media is a huge challenge, but just like artificial intelligence, it’s part of our reality now. Journalists must do everything they can to make sure the voice of truth cuts through the noise. These platforms aren’t going anywhere, so we need to learn how to use them effectively to fight for facts and deliver accurate information.”

Which meetings from your journalistic career stand out the most?

“Very often, when you cover a story, you end up staying in touch with the people involved for years. I’ve had many memorable encounters, but the ones that stand out most right now are my conversations with the mothers of fallen American volunteers who went to Ukraine to fight. Some of them died, and now their mothers, fathers, and other relatives come to the U.S. Congress, trying to convince lawmakers to keep supporting Ukraine. Those conversations were incredibly powerful and emotional.

I’ve also spoken with American veterans who ended their military careers in the U.S. and chose to go fight in Ukraine. Some are still on the front lines. We talked about what inspired them to join the fight—how they connected with Ukraine’s struggle and felt called to stand up for justice. These were some of the most powerful interviews I’ve done—talking to people who cross an ocean to defend democracy in a country not their own.

Another memorable experience was interviewing Congressional chaplains. I actually did a full set of stories on this. Both the House and Senate begin their daily sessions with a prayer, led by appointed chaplains who rotate over time. There’s one chaplain for the House and another for the Senate. I interviewed both. These days, they often pray for Ukraine at the start of sessions. In particular, Chaplain Margaret Kibben in the House prays for Ukraine every Wednesday. Remember I told you Wednesdays are the busiest days in Congress?”

Does that mean Catholics and Protestants pray together in Congress?

“Technically, yes. And not just them—there are also Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and other religious lawmakers.

Formally, congressional chaplains are nonpartisan, nonpolitical, and are not supposed to promote any specific denomination. However, historically, all congressional chaplains have been Christian. Currently, House Chaplain Margaret Kibben is a Christian but doesn’t represent any particular denomination, and Senate Chaplain Barry Black is the first Seventh-day Adventist to hold that position.

There’s also a long-standing tradition in Congress of inviting guest chaplains from various faiths to deliver opening prayers in the House or Senate. These guests have included not only Christians, but also Jewish, Muslim, and other religious leaders.

During my interview, I asked if a Ukrainian priest had ever been invited before. They said no. Not long after that, for the first time in its history, the Senate invited a Ukrainian Orthodox priest and military chaplain, Volodymyr Shtelyak, to deliver the opening prayer.”

What would you advise young Ukrainian journalists who dream of an international journalism career?

“Study multiple languages—take that very seriously. It’s incredibly helpful for international journalists to know several languages. I speak five: Ukrainian (my native language), Russian (which was imposed by the occupiers), Hebrew, English, and Spanish. The last two are the most dominant in my work. I highly recommend other journalists learn English and Spanish as well. These are foundational global languages that open doors and help you understand others.

Once, during the UN General Assembly, I had a brief interview with French President Emmanuel Macron. I asked him a question in English, and he deliberately responded in French. Because I speak English and Spanish, I was able to intuitively understand his answer and follow up with another question. That moment proved just how valuable language skills are.

I also recommend reading a lot about the international organizations you’re interested in and staying closely tuned to the news cycle of the country or region you hope to cover. Get as much hands-on experience as possible—apply for grants, scholarships, fellowships, and journalism awards. Theory is important, but there’s no substitute for real-world practice.

And most importantly—believe in yourself. To anyone in Ukraine who wants to pursue international journalism: you are needed! Don’t listen to people who say your stories won’t matter or won’t be seen. They will. The world is paying attention. So go for it, move forward, and don’t hold back—because there are actually very few of us working in this space.”

Interview by Maksym Stepanov, NUJU Information Service

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post