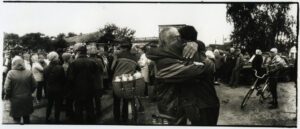

For the first week or two, I just observed what was happening, but then I realized that I needed to document it all. At the beginning of the war, anyone with a camera or phone often faced hostility—not just from locals, but also from the military, police, and others. So, I had to approach it carefully, step by step. Eventually, I was able to start filming. Once you start documenting, you also need some sort of authorization to continue doing it.

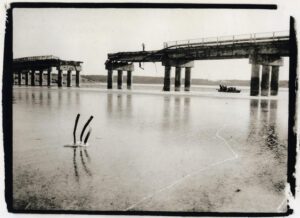

I’ve always dreamed of filming war. I used to think that war would eventually come to us, and my motivation was to ensure this story remains for future generations. My goal was to capture this war as beautifully as possible, in line with my vision. Ultimately, I wanted to turn it into my own book. I shoot on black-and-white film, develop it myself, and print it in a darkroom. When I scan my prints, that’s when the photo becomes ready to show. The idea behind creating a book is to make something archival, something that will remain a part of history. A book has a certain permanence. Even if an archive is destroyed—say, by a bomb hitting the building—a book can survive and preserve the story you’ve captured. This isn’t something unique to me. Many people filming war have similar experiences. Tragically, more than 70 journalists and photographers have already been killed in this war. It’s a harsh reality, but the experience itself shapes your vision. It’s unpredictable—you never know if something will happen today or not.

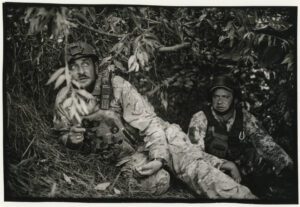

I remember one particular day vividly. We were in the Pokrovsk region, filming during an artillery attack. We were doing our job when suddenly the shelling intensified, and one of the shells hit our dugout. Shrapnel from the explosion came through a ventilation hole and struck Olga. Those of us who weren’t wearing protective gear sustained injuries, and she was seriously wounded. She’s still rehabilitating her arm. Thankfully, everyone survived, but it was a stark reminder of the risks we face. I don’t do this for money. I don’t need to zoom in for dramatic shots; I film because I love it. It’s something deeply important to me. However, I wouldn’t say I’m ready to die for it. Safety must always come first. What keeps me going is the creative process—it’s what fuels me, even on tough days.

During the Maidan protests, it was easy to capture the energy of the moment because so much was happening in one concentrated space. In contrast, war zones require a different mindset. If you’re a photographer, you need to constantly assess the risks and take care of your safety. Plan your shots carefully and decide how much danger you’re willing to face. If a shot is absolutely necessary, you take it. If it’s too dangerous, it might be better to wait. Remember, if you lose your life, your work stops there. People might remember you for a week or so, but that’s it. So, prioritize your safety above all else.

Created as part of the project “Raising awareness among target groups in Ukraine and abroad about Russian war crimes against journalists in 2024 and increasing public pressure for the release of captured journalists”, which is implemented by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine with support of the Swedish non-profit human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post