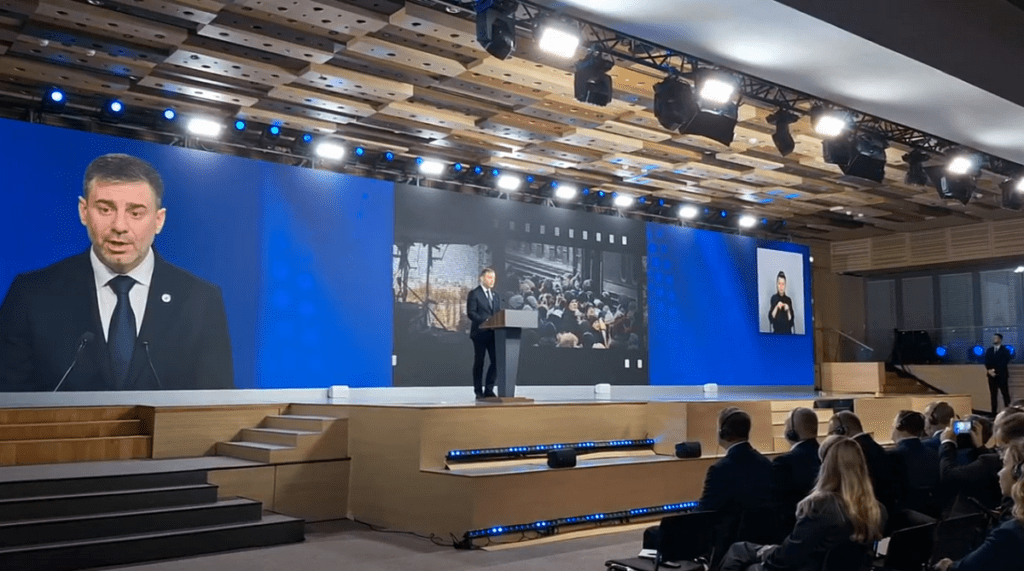

A large-scale International Human Rights Conference called Decade of 2014-2024. Reclaiming Human Rights. Preserving Democracy was held in Kyiv.

Representatives of Ukraine and international organizations took part in the event: government officials, diplomats, representatives of public organizations, human rights activists, journalists, etc.

At the beginning of the conference, the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, made an online congratulatory speech. Not only did the President draw attention to russia’s crimes against Ukrainians in captivity, but he also noted that “many people in the world are still not making every effort to stop this crime, return people, and punish russia for everything it has brought.”

In his speech, the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, Dmytro Lubinets, appealed to international colleagues to help defend human rights and democracy, “and do it here, in Ukraine. Otherwise, this darkness will come to you,” the Commissioner emphasized.

The Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Alain Berset, the Ambassador of Japan to Ukraine, Masashi Nakagome, the UNDP Deputy Resident Representative in Ukraine, Christophoros Politis, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, also addressed the participants with welcoming words.

In the lobby of the Parkovyi Exhibition and Convention Center, where the conference was held, the attendees were able to familiarize themselves with photo exhibitions that vividly illustrate the work to free Ukrainians from captivity. The Pick up the Phone stand attracts special attention, where one could hear piercing calls from the front, occupation, and captivity.

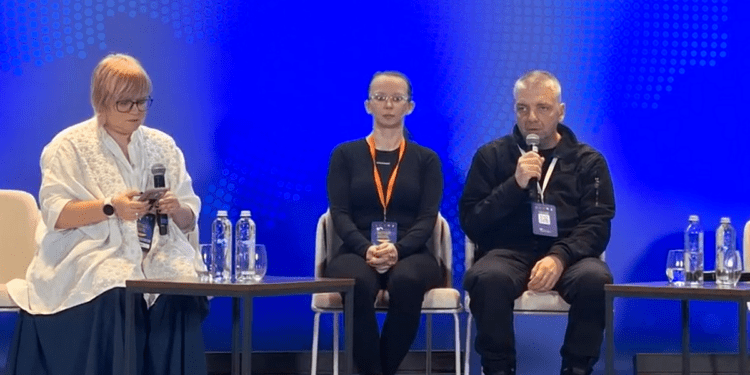

During the conference, discussion panels were held to discuss the topics of searching for and returning Ukrainians from captivity, reintegration of released civilians, protection of the rights of Ukrainian children, etc.

Panel discussion on the topic of searching for and returning Ukrainians from captivity

At this discussion, journalist and human rights activist Maksym Butkevych told the story of his time in russian captivity. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, he stood up for the defense of the Motherland, was soon captured, and received a sentence of 13 years by “the Luhansk People’s Republic’s court.”

“My sentence was the shortest. It was a kind of test of how many years of imprisonment can be given under this set of articles of the Criminal Code of the russian federation. Other guys who received a sentence under the same articles received more: 14 and 15 years,” said Maksym Butkevych.

The journalist continued the story by saying that no one was surprised by the absurd circumstances of the case, such as “throwing a hand grenade 200 meters away,” “firing a Grad at 60 meters away,” etc. “I had state-appointed lawyers, but I didn’t see any of them; I just signed what they prepared in advance.”

According to the human rights activist, violence and beatings (the main method of fabricating the case), the implausibility of the circumstances indicated in the case, and a different attitude towards imprisoned citizens of the russian federation were common to both civilians and prisoners of war.

“It seemed like some kind of theater of the absurd was taking place,” said Maksym Butkevych. Already in court, the journalist dared to ask why he was being brought in if the case was fabricated. And he received the answer that there was a procedure.

Captivity and protection of rights

As the media person noted, captivity was a surprise and a test for him at the same time.

“Captivity also became for me an experience, despite which I tried to extract everything useful for me as a citizen, activist, human rights defender, in order to then apply this experience, if possible, to efforts to free other of our fellow citizens from captivity: both military and civilian,” said Butkevych.

In the cells of the Luhansk remand prison, where prisoners of war were kept separately from others and each other, it was impossible to obtain any information. For example, what awaits the prisoners or about events taking place at home. Usually, the prisoners learned some fragmentary information from those who were captured later. Some information was reported by the guards in order to put pressure on the detainees, for example, about massive attacks on the energy infrastructure of Ukraine.

“The guards used beatings, and that’s how we learned what was allowed and what wasn’t,” the journalist comments on the situation of how the prisoners learned the rules of internal order in the remand prison.

Maksym Butkevych says that most prisoners of war do not see representatives of human rights organizations. He was “luckier” than most. The journalist recalls a visit by a representative of the UN mission, which turned out to be indicative. After its completion, nothing changed in the attitude towards prisoners of war or the conditions of their detention.

The journalist also shared the details of a meeting with the “human rights commissioner of the LPR.” During such a visit, he asked whether prisoners could have the right to read the remnants of Ukrainian literature that are in the colony’s library. The “human rights activist” replied that this issue was “interesting” and “needs discussion.” After this case, within a few weeks, all Ukrainian-language literature from the library disappeared.

On what keeps prisoners “afloat”

“What kept all prisoners “afloat” is the belief that they will soon be released and the knowledge that they are remembered, that they are spoken about, written about, and thought about…,” said Maksym Butkevych.

According to him, the fact that he and another prisoner were exchanged was important for those who remained. It gave them hope that release was possible at all, the journalist emphasized.

Larysa Portianko, NUJU Information Service

Photo by the author

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post