Anatoliy Zhupina and Oksana Pavlenko are a father and a daughter who dedicated their lives to developing one of the most influential publications in the Kherson region – the newspaper Novyi Den (New Day). However, the full-scale invasion of Russia brought significant changes to their destinies. The publication’s printing ceased, and they found themselves fighting for survival.

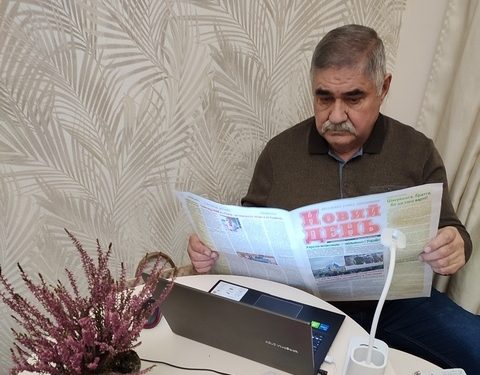

Anatoliy Zhupina is a journalist with 50 years of experience. In 1996, he became the head of the independent newspaper Novyi Den, which became one of the most popular publications in the Kherson region. In 2008, he was awarded the honorary title of “Merited Journalist of Ukraine.” Inspired by her father’s example, his daughter Oksana Pavlenko also decided to become a journalist and currently serves as the deputy editor.

“In the early days of the war, it seemed like it wasn’t our life”

…Just a few hours before the first explosions, the editorial team managed to publish the latest issue of the newspaper and celebrate the accountant’s birthday.

— On February 23, we worked and then congratulated our accountant on his 60th birthday. So, as you can understand, there were no thoughts about anything terrible then. We went home, and the next morning, I received a message that Russian forces had crossed the border from Crimea into Ukraine. Everything changed rapidly in the first few hours. They first captured the Kakhovska Hydroelectric Power Station, then the North Crimean Canal, and by noon, fierce battles were already raging on the outskirts of Kherson. I told my colleagues not to come to work and to work remotely on our newspaper’s website, — recalls Anatoliy.

No one had time to recover when Kherson found itself under siege the next day. Any attempt by people to leave the city ended in death. The same fate awaited the desperate resistance put up by the Kherson youth, which resulted in automatic gunfire.

— In the early days of the war, it seemed like it wasn’t our life. Many civilians were killed as they tried to leave because they didn’t realize how dangerous it could be. Our boys bravely defended, understanding that if the occupiers crossed the Antonivsky Bridge, consider the city taken. The brave ones confronted the invaders with Molotov cocktails – the so-called ‘Banderivtsi’ stripes -, but unfortunately, they were unarmed, and over 150 boys who tried to defend us lost their lives, — Oksana shares.

As soon as the Russian forces entered Kherson, active preparations for the pseudo-referendum began. However, the people of Ukraine, who are not accustomed to being herded like cattle, revolted, raged, and took to the streets in protest.

— People came in thousands, with flags, slogans, and banners saying ‘Away, occupiers! Kherson is Ukraine!’ We were very united. What struck me the most was when one of our young Ukrainians jumped onto a BTR (armored vehicle) with a flag, and others started supporting him and applauding… It was very brave, — the journalist recalls.

“I’m sitting behind the wheel, and my 12-year-old son is beside me, holding a cross while I pray out loud. That’s how we were driving.”

The Russians were not going to admit that the occupiers were not welcome in Kherson. They could only follow the old, tried-and-tested scripts used in Moscow and St. Petersburg protests – persecuting, kidnapping, and arresting the most active ones to throw them into the basements. Oksana and Anatoliy knew that journalists would also be ‘handled’ by informants and collaborators working for the Russians. So, Oksana came up with her first safety rule.

— Our neighbors said, ‘Come to us; we’ll hide you if needed.’ Of course, no one went alone, but we tried to cover our faces with hats and hoods when we went out. It was still winter, very cold. There were people in the city who had come from the occupied territories. They had already been through such situations, so they gave us life advice: ‘When you leave home, don’t draw attention to yourself, you need to be inconspicuous,’ — Oksana reveals, admitting that during those days, she worried more about her parents’ safety than her own, especially when she found out that the Russians had visited her father three times.

— My wife and I had moved to our daughter’s place, but I left the car in the garage, not far from our home. So, when they came for the third time, I was walking out of the garage, and people started shouting, ‘Where are you going? They came for you.’ After that, we decided once and for all that we had to leave. I really didn’t want to leave the city, and I needed to settle things with my colleagues, but on March 22, we finally left. My wife, daughter, grandson, and our niece – we were all in the car, — our interviewee shares.

The family successfully traversed the safest route along the Dnipro River, passing eight checkpoints. Only one village stood between them and free Ukraine, but the road went over a dam heavily bombarded by the Russian invaders.

— We drove in a convoy of four cars. I was in the front, and behind were my parents, sister, and another family. We were warned that we had to cover this stretch as fast as possible. Honestly, I had never driven so fast in my life. Imagine me in a red car, with a white tulle draped behind me like a veil – the only thing identifying us as civilians — shared journalist Oksana Pavlenko. — I’m sitting behind the wheel, and my 12-year-old son is beside me, holding a cross while I pray out loud. That’s how we were driving. At that moment, people asked me, ‘Where did you learn to drive so fast?’ And I said, ‘It’s a situation where you either fly or ‘fly away.’ And when we saw our military, people from different cars started offering them treats, hugging them, giving them packages with various goodies, shouting ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ The joy was indescribable.

The journalists and their families eventually reached Mykolaiv and then Lviv, where acquaintances welcomed them. They were offered assistance with housing and all the necessities for the initial period. Later, the entire newspaper team also left occupied Kherson to gradually return to work.

— All the equipment and necessary tools for work, of course, remained under occupation. I told my colleagues to take the most essential documents and asked them not to leave anything behind. But where could they take the furniture, the equipment? We had a huge two-story editorial office and a press club, and it was impossible to anticipate where to hide everything that was taken from there. Some took things to their garages as I did, but the occupiers came and took everything or destroyed it. They broke the doors and took the most valuable things if there were no owners. So, when we arrived in Lviv, we came with empty hands, but the Lviv Journalists’ Solidarity Center significantly helped us. They provided us with equipment, and we were able to resume our work,— said Anatoliy Zhupina.

— Before, we only had a newspaper and a website, but our colleagues in Lviv helped us create a Facebook page, NewDay.ua, and a Telegram channel. In September, we launched a new website, — added Oksana.

“For the printed word, which people were accustomed to trusting, they were waiting there”

Kherson was under Russian occupation for nine months. On November 11th, Ukrainian forces liberated the city. After the Russians left, there was no electricity, heating, or drinking water in the city, but the most important thing was there – freedom. And a week after the liberation, the beloved newspaper Novyi Den returned to the people of Kherson.

— It is very important because there was no Ukrainian television, Ukrainian radio, and Ukrainian newspapers or websites in the city for a long time. Therefore, people were eagerly waiting for the printed word, which they were accustomed to trusting. At the first opportunity, we will return home and work there. We are looking forward to this moment because Kherson is Ukraine, — confidently say Anatoliy Zhupina and Oksana Pavlenko, journalists of the Kherson newspaper Novyi Den.

Anatoliy Zhupina and Oksana Pavlenko, a father and daughter, dedicated their lives to the newspaper Novyi Den in Kherson, Ukraine. However, the Russian invasion disrupted their work, and they struggled to survive during the occupation. They experienced the challenges and dangers of reporting under occupation, with attempts to suppress free media. Despite the difficulties, they stood firm in their belief in the freedom of the press and their commitment to delivering accurate information to the people.

Eventually, when Kherson was liberated, the journalists and their newspapers returned, bringing hope and reliable news back to the city. They continue to look forward to resuming their work in a free Kherson, emphasizing that their beloved city is an integral part of Ukraine.

This series, titled Executed Free Speech, is created as part of a project Drawing Ukrainian And International Audience’s Attention To Serious Violations Of Human Rights And Crimes Against Journalists And Mass Media By The Russian Federation, which is performed by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, with support from the Swedish non-profit organization Civil Rights Defenders.

JOURNALISTS ARE IMPORTANT. Stories of Life and Work in Conditions of War is a cycle of materials prepared by the team of the NUJU with the support of the Swedish human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

#CRD

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post