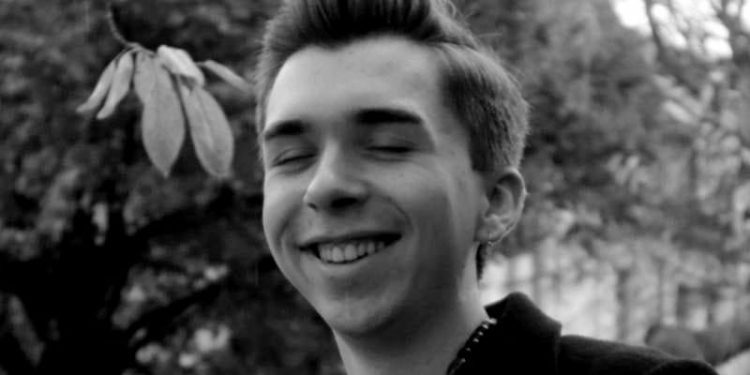

Before the full-scale war, Yehor Kuzmin studied journalism at the university and wrote “for himself.” However, during the hostilities, he published two magazines and created a landing page about events in Ukraine. This is how the life of the student-journalist Yehor Kuzmin changed.

Diary from Mariupol

Yehor hails from Donetsk, specifically from the town of Selydove. However, he lived in Mariupol and pursued his studies in journalism at Mariupol State University. He experienced a month of living under occupation but managed to escape to the territory under Ukrainian control. Initially, he relocated to Vinnytsia, where he, together with a colleague, established an online journal called “Ukrainizuvatysia” [Ukrainize or to become more Ukrainian].

— This publication is about how Ukraine and Ukrainians respond to the war, how foreign celebrities and organizations support Ukrainians during the war, and it also delves into the culture amidst the war. In some of our publications, we also talk about volunteers, — says Yehor Kuzmin.

The full-scale war brought significant changes to Yehor’s life, altering his approach to journalism. He now writes for the media and serves as a communications specialist at the NGO Ukrainian Volunteer Service.

– I wrote for an online magazine called “Platforma,” and a recent piece was published in the Kharkiv-based media outlet “Nakypilo.” My first piece, written in the spring, was essentially an online diary of my experiences in Mariupol. I spent a month there during the blockade and could only leave on March 23rd, initially to the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) territory and then to Ukraine. This journey took me through Russia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. In Mariupol, I maintained a daily journal in a regular notebook, recording my thoughts every day. I did this to document the details as a journalist, ensuring I wouldn’t forget them and to capture all my feelings, — explained the young man.

Yehor’s concern grew when Putin officially recognized the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR). Many Ukrainians didn’t immediately grasp the significance, but discussions about an impending conflict were already happening.

— We didn’t grasp the situation’s gravity or the danger it posed initially. There were initial border breaches and sporadic shelling, but it wasn’t widely discussed. On February 24th, I received a worried call from my mom at 6 in the morning while I was in my dormitory. She asked about the situation, and I wasn’t aware of the initial explosions; it was my mom who informed me about the invasion. Initially fearful, I quickly gathered myself and checked news websites for updates. I learned that there had been shelling in many Ukrainian cities. Soon, I heard a series of explosions in Mariupol. I didn’t anticipate the scale of what was unfolding. I initially thought it might last a day or two and resolve somehow. However, by the second or third day in Mariupol, it became clear that this would not pass quickly. Leaving the city became a challenge. I stayed, hoping for a robust defense, but events unfolded differently from our expectations, — confesses Yehor Kuzmin.

Later, journalism students had to move from the dormitory to a garage.

— We quickly gathered essential supplies. In the first few days, the city lost power, and our dormitory had no gas or heating. To address this, our dormitory manager worked with the university administration to bring in a makeshift heater installed in a garage, which became our only source of warmth and a place to cook. The water supply disappeared about 4-5 days after the invasion, forcing us to walk to a distant water station for supplies. We were somewhat fortunate as not everyone had returned to the dormitory due to the start of a new semester. After enduring three weeks of the blockade, we, along with our dormitory manager, scavenged leftover provisions. Unfortunately, stores had been looted and vandalized, making it impossible to purchase anything, — our interviewee explained.

Departure through Russia

Yegor contemplated leaving when the city was running out of food. Humanitarian aid wasn’t reaching Mariupol, and there were no green corridors towards Ukraine. The only option was to travel through the occupied territory into Russia and then on to Europe.

— To leave, we endured a waiting list with about three buses departing daily. On the first day, we couldn’t board, so we spent a night in a damaged hospital with both peaceful Mariupol residents and the occupiers, which was a nightmarish experience. The next morning, we managed to depart for Donetsk. There, we stayed at a refugee camp in a school for almost a week, awaiting document verification and database entry. Later, we went to my acquaintance’s home. Being only 17 and not yet of legal age, I faced relatively few issues during these travels. Still, I underwent checks at checkpoints, including showing my hands and legs to ensure no military distinctions. Crossing the border into Russia and the occupied territory went smoothly. However, we encountered minor complications at the Russia-Latvia border, where they extensively scrutinized our documents. It was nerve-wracking as they held our documents and had us wait in a corridor, and we were uncertain whether they’d return them or permit entry into Latvia. Fortunately, it resolved within half an hour, and we crossed the border on foot, — Yehor recounted.

“Returning to the Donetsk region is difficult for me.”

Currently, Yehor resides in Kyiv and attends his university, which has relocated to the capital. His parents still live in their hometown, Selydove, in the Donetsk region. Fortunately, the town remains under Ukraine’s control.

— A lot has changed during this time; I haven’t seen my parents for nearly eight months. We first met in Kyiv in September when they came to visit me. Returning to the Donetsk region is difficult for me; it seems that if I go back, something might happen, and I won’t be able to leave. After what I experienced in Mariupol, I don’t even know when I’ll be able to return there, — confesses the young man.

Yehor Kuzmin’s current plans involve balancing his education with work and staying in this flow. After finishing university, he aspires to work in journalism, particularly in print media, as that’s what he enjoys the most.

— Someday, when I have enough experience, I’d like to have my own publication — the student dreams.

For now, he believes in victory and eagerly awaits it. When he was in Mariupol, he yearned to see Ukrainian flags and hear the Ukrainian language. Now, he dreams that all of this will return to the occupied territories.

— I had the opportunity to stay abroad, but I still returned to Ukraine because I can’t live without it. I believe in victory and work towards it with my volunteer efforts and job, — says our interviewee.

The first thing Yehor wants to do after victory is reunite with all his friends who have scattered across different parts of Ukraine and the world.

This series, titled Executed Free Speech, is created as part of a project Drawing Ukrainian And International Audience’s Attention To Serious Violations Of Human Rights And Crimes Against Journalists And Mass Media By The Russian Federation, which is performed by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, with support from the Swedish non-profit organization Civil Rights Defenders.

JOURNALISTS ARE IMPORTANT. Stories of Life and Work in Conditions of War is a cycle of materials prepared by the team of the NUJU with the support of the Swedish human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

#CRD

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post