For 45 days, the journalist Vitalina Zinkivska lived through shelling in her hometown of Kharkiv. In the early days of the conflict, she began volunteering by weaving camouflage nets and sorting humanitarian aid for the soldiers. This could have continued until victory, but her health eventually faltered due to the daily stress. Vitalina shared her experiences with the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU), discussing a stranger’s car, rescuing children, a heart attack, and the “net hub.”

“What are you doing? Don’t worry, war has begun…”

Vitalina Zinkivska dedicated 27 years of her life to journalism. She served as a Ukrainian Radio correspondent in Kharkiv for a long time. In the past two years, she was the lead specialist in the content quality monitoring department at the National Public Television and Radio Company. However, her work did not prevent her from assisting the Ukrainian Armed Forces since 2014.

— I understand the need for this very well. In our volunteer association, there was the wife of a serviceman, and their son was also in the military. When the war started in 2014, he joined a tank unit. During one of their missions, our nets helped save the lives of several soldiers. That’s why I will never leave the volunteer cause,— the journalist assures.

Vitalina learned about the war’s start from a fellow volunteer she knew well. The shock she felt surpassed words.

— A friend called me with this strange voice as if she were a kindergarten teacher. ‘Vitalina, hello. What are you doing? Don’t worry, war has begun… Wake up. Quietly gather your backpack, put everything you need in it…’,— Vitalina recalls the events of February.

At that time, the journalist lived in an apartment with her husband, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson. When the acquaintance woke her up, they were all already up and about. They were trembling from shock and fear. Russian fighter jets circled above the house, and the family decided not to wake their mother.

— I’m a night owl, I go to bed late and get up late, and they decided not to wake me up, as if saying, let Mom sleep a bit longer during ‘peaceful hours.’ So I woke up when Kharkiv was already being bombed when Russian bombers were flying overhead. How did I manage to sleep through all of this? I was a bit embarrassed,— says the journalist.

Leaving the center of Kharkiv, where Vitalina’s home was located, had become nearly impossible by that time. The city was gridlocked in traffic. Walking to the train station was extremely dangerous. The opportunity for Vitalina and her family to escape the city only arose on the third day of the war.

— We had a car parked outside our windows. Its owner called us, saying, ‘Leave, just take my two girls with the dog.’ I literally pushed my children: my son, daughter, son-in-law, and grandson, so that they would finally leave. And they left. There was no room in the car for my husband and me, of course, but it didn’t matter to me because the safety of the children, especially my grandson, was the top priority. He would often have nosebleeds during each shelling, and there could be up to 65 shelling incidents in a day. Can you imagine?— Vitalina recounted.

“Weaving Camouflage Nets Soothed Me – Even During Intense Rocket Attacks on Kharkiv”

After ensuring her children’s and grandson’s safety, Vitalina found solace in volunteering. With the Public Television and Radio Company on hold due to the circumstances, she immersed herself in weaving camouflage nets, which provided comfort even amidst Kharkiv’s intense rocket attacks.

— I could take the net base from our already destroyed headquarters, the base where we tied the ribbons, took the materials, brought them home, hung them on the wall, and started weaving. For me, it’s like meditation. Firstly, it calms you down, and secondly, you feel you’re doing something necessary. Later, people from Western Ukraine started contacting me, asking me to send them nets. I forecasted this correctly as military personnel began calling, in dire need of these nets. I was both weaving them and acting as a ‘net hub,’— shares the journalist and volunteer Vitalina. — Neighbors got involved in the effort, asking to be taught how to weave. Then, a classmate of mine approached me and said that his parents also wanted to join our group. In short, a significant community formed around these nets. Everyone wanted to be helpful and understand that they weren’t just enduring danger but doing something genuinely important.

— I retrieved the net base from our demolished headquarters, where we tied ribbons, brought the materials home, hung them on the wall, and began weaving. It’s like meditation for me. It calms you and gives you a sense of purpose. Soon, people from Western Ukraine requested nets. I anticipated this, as soldiers urgently needed them. I wove and acted as a ‘net hub,’— Vitalina, the journalist and volunteer, explains. — Neighbors joined, wanting to learn. A classmate’s parents also joined. A significant community formed around the nets. Everyone wanted to be helpful, realizing the importance of their actions.

There were so many nets handed over by volunteers that they had to be laid out on the stairs at the entrance Photo: Vitalina Zinkivska.

“It’s Time to Save My Own Life”

After weaving nets for 45 days under shelling, Vitalina experienced a heart attack one day, and the ambulance couldn’t come because medical personnel were tirelessly assisting the wounded after incessant bombardment. She realized it was time to consider her own life.

— After enduring 45 days of shelling, eating, bathing, and sleeping under it… I lost 7 kilograms, and my husband lost 20. My heart started acting up, and I felt unwell. When I tried to call an ambulance, they said, ‘Excuse me, a heart attack? We have many wounded after the shelling. All the ambulances are there.’ And I thought, if something happened to me here, I would create a huge problem for my children. So my husband and I left for Ivano-Frankivsk to our son,— recalls Vitalina.

Adapting to a peaceful life was challenging for Kharkiv residents. Every loud sound was perceived as enemy shelling.

— Once, in the Carpathians, I sat in a bus. It was April, and rain was predicted for the day. Ignoring the forecast, I went. Suddenly, a fierce thunderstorm erupted as we began our journey. Lightning ahead… A sensation of impending air raids and explosions… I sat in the front seat, curling up in fear,— Vitalina recalls with a touch of pain. — Then I realized it was just rain and thunder. I straightened up, finding the whole bus looking at me. People assured me, ‘Don’t worry, it’s just rain.’ They understood my perspective as someone who had experienced shelling and treated me with sympathy.

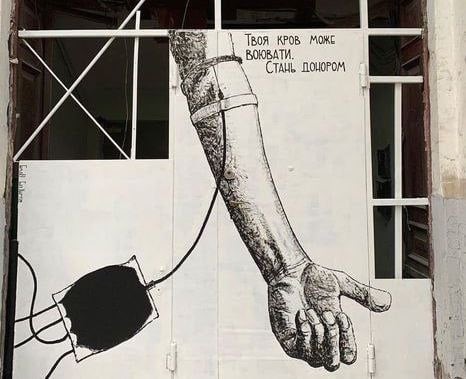

“Your Blood Can Also Fight”

In May, Vitalina’s son, the well-known Kharkiv artist Hamlet Zinkivskyi, decided to return to Kharkiv and join a volunteer battalion. His mother bid him farewell with tears in her eyes.

— On May 7, he decided to return to Kharkiv. Imagine, it’s almost May 9, we’re all waiting for provocation from Russia, and he’s going… Of course, there were tears, sleepless nights, but he’s there. He’s already created over 30 street art pieces in the city. One of them is a mural in support of blood donation: a huge painting with the words ‘Your blood can also fight.’ After this artwork appeared, queues formed at blood transfusion stations in Kharkiv,— says Vitalina with pride and tears. — Even the Ministry of Health turned to him, asking for permission to use this slogan for a nationwide blood donation campaign. But he does more than just paint. He’s also responsible for supplying equipment and weapons to his battalion. I know and understand that he’s involved in very important tasks.

Back to Work Again!

In her new location, Vitalina met many familiar faces, and in July, she finally returned to work. The Ivano-Frankivsk Center of Journalistic Solidarity team also helped her arrange financial aid from the NUJU and provided necessary supplies and school equipment for her grandson. The woman also found like-minded people to continue her volunteer work with.

Here, we have a fantastic team that weaves camouflage nets too. But the local volunteers use slightly different equipment, so we decided I’d mostly prepare materials while they knit. In my free time from work, I join them to work together and connect,— the journalist explains.

“I Will Return to Beloved Kharkiv”

Despite her love for the hospitable Ivano-Frankivsk, Vitalina’s biggest dream is to return to her hometown of Kharkiv.

— I know our apartment is intact because a boy volunteer lives there now. He says that the heating has been restored to the building. We plan to return in spring, but I wouldn’t know exactly when. With immense gratitude, and beautiful memories, I will eventually leave Ivano-Frankivsk and return to our wounded, suffering, but infinitely beloved Kharkiv,— concludes our interviewee.

This series, titled Executed Free Speech, is created as part of a project Drawing Ukrainian And International Audience’s Attention To Serious Violations Of Human Rights And Crimes Against Journalists And Mass Media By The Russian Federation, which is performed by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, with support from the Swedish non-profit organization Civil Rights Defenders.

JOURNALISTS ARE IMPORTANT. Stories of Life and Work in Conditions of War is a cycle of materials prepared by the team of the NUJU with the support of the Swedish human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

#CRD

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post