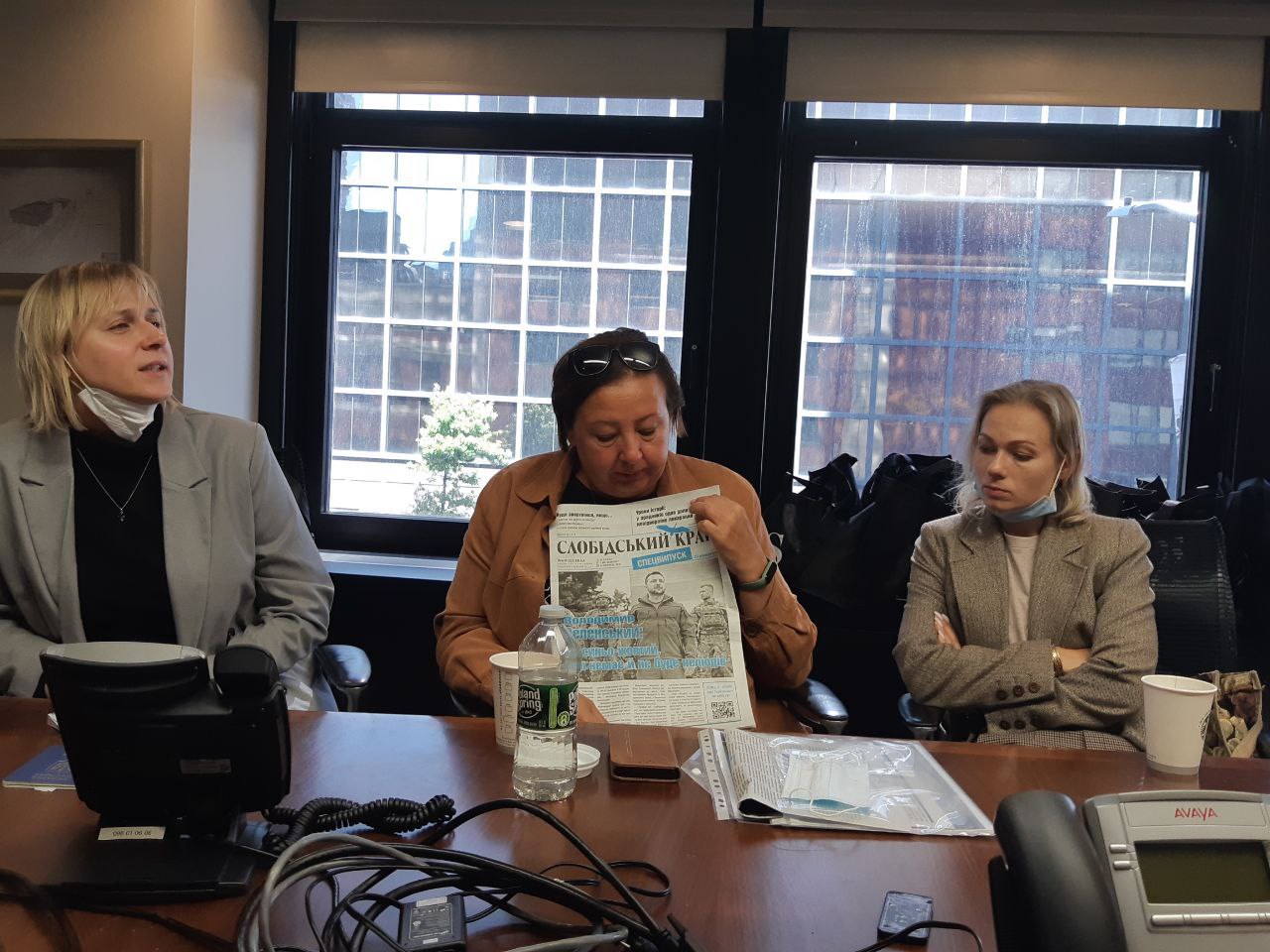

Larysa Hnatchenko is the chief editor of the oldest publication in the Kharkiv region, “Slobidskyi Kray.” The major conflict erupted just when the latest issue of the newspaper was released, and the editorial team had to begin work on the next one. Could anyone from the media have foreseen the unexpected blow that the neighboring country would strike at Ukraine?

“They began bombing Kharkiv, and saboteurs were literally running outside our windows.”

On February 23rd, Larysa returned home late from work as she had been submitting the newspaper for printing. She was tired and almost immediately fell asleep.

— In the early hours of February 24th, around 4:30 AM, a journalist from Balakliia called me and informed me that a full-scale war had begun, and bombs were already falling on their city. I started calling my friends and colleagues because there was already a lot of noise in our region. We understood that a significant enemy force had gathered near our area. One of our journalists even said he would go to fight as soon as it all started. This conversation was on Monday, and by Saturday, he was already at the military enlistment office. I live on the outskirts of Kharkiv, and about half an hour after I received the news of the war’s start, cars started moving along the road under my windows. It wasn’t even a traffic jam; there were just countless cars. People were trying to leave. Then they started bombing Kharkiv. There were many sabotage groups in the city, and saboteurs were literally running under my windows, — began her story, Mrs. Hnatchenko.

The heavy shelling didn’t stop, whether it was day or night. The most terrifying moments were during the air raids.

— In our area, we had two extremely dreadful nights: during the first one, nine rockets hit, and during the second, there was an aerial bombardment. During the raid, my daughter and I sat huddled together in the corridor. Everything around us was cracking and falling, and the building was swaying. I was in such a state of shock. It’s very frightening when a plane flies over you and drops bombs, — recalls the journalist.

When endurance became unbearable and fear had completely taken over her body and mind, Larysa decided it was time to leave her home.

Larysa received a call from a colleague about an evacuation bus. She and her daughter quickly packed, caught the bus towards Poltava, and arrived in Valky. Housing was scarce due to heavy bombings in Kharkiv. Larysa’s relatives in Kremenchuk found them an apartment, and volunteers provided transportation.

Once settled in their new place, Larysa resumed work. Her daughter, unexpectedly to both of them, became an editor and assisted her mother in managing the publication.

— For two weeks, we worked solely through social media. My daughter quickly took on the role of a website editor and helped me tremendously. Meanwhile, I joined the volunteer movement in Kremenchuk. There, by the way, there are many fellow residents from our region, including Izium and Balakliia. People don’t sit idle, — Larysa shares.

“People aren’t coming back because, for many of them, there’s nowhere to return to.”

Larysa lived in relatively safe Kremenchuk, but her heart and thoughts were always in her native Kharkiv. She later started visiting her home and returned for good in the fall.

— We sought help from anyone willing. The first support came from journalists at a Californian media outlet where we had interned in 2019. They pooled funds, which I distributed to help people leave. Numerous organizations later offered assistance. Special thanks to the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU), which not only provided financial aid but also motivated us to seek support from other groups. Currently, six colleagues remain in Kharkiv, two in the Kharkiv region, and others scattered across Ukraine and abroad. One colleague had already begun traveling before the war and couldn’t return. Many aren’t returning because they have nothing to return to. Some are from the Northern Saltivka area of Kharkiv, frequently targeted in attacks, and one person is from Chuhuiv, where their home no longer stands. Another colleague relocated to Germany and left our team. A colleague with children was in Balakliia, a city heavily bombed. We organized her evacuation with support from UK volunteers and guidance from our colleagues at the local media outlet ‘Visti Zmiivshchyny,’ who assisted her and the children from one shelter to another via phone calls. They are all alive but endured significant stress, especially the children, — the journalist explained.

“When people discovered the truth, it was a shock.”

Before the full-scale Russian invasion, “Slobidskyi Kray” was published twice a week. In June, with support from the organization Irex, the team managed to resume printing the newspaper. However, it now comes out once a week but spans 16 pages.

— Ukrposhta [Ukrainian Postal Service] isn’t available in many parts of the Kharkiv region, especially in war areas like Dvorichna and Lyptsy. Even in areas where Ukrposhta is operating, it’s limited to pension distribution, so subscribers aren’t receiving their newspapers. To bridge the information gap, we rely on volunteers and Nova Poshta [a leading courier and logistics company in Ukraine] to deliver newspapers for free where possible. Additionally, the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy partnered with us to create special issues for the de-occupied territories. In these issues, we provide insights into events both in Ukraine and worldwide. People had previously received a misleading newspaper titled ‘Kharkiv Z,’ falsely claiming that Zelensky no longer existed and Ukraine had disappeared. When they discovered the truth, it was a shock. We also offer guidance on accessing social payments and share volunteer contact details. This initiative received support from donors, allowing us to produce four special issues distributed by volunteers and military personnel. — the editor tells.

“We hope the state will make changes regarding printed newspapers.”

According to Larysa, another crucial aspect of their work is supporting communities.

— We highlight occupied communities and those still affected by war. Our aim is to raise awareness and help these communities access international aid beyond what the central government provides. We also share stories of individuals in need of medical support, protective gear, and more. When we succeed in bringing attention to their plight and offer assistance, we receive valuable feedback from our readers. We also assist in connecting them with the prosecutor’s office for identifying deceased relatives, although it’s emotionally challenging. We’ve advocated for printed publications, especially in rural areas with limited internet access, for years. Unfortunately, the destruction of printed media, sometimes by ‘Ukrposhta,’ hindered this. When the occupiers came, they quickly distributed their own newspapers. We hope the state will make changes to ensure wider distribution of pro-Ukrainian press, particularly in rural and border areas, — concluded Larysa Hnatchenko, the chief editor of “Slobidskyi Kray,” the oldest publication in the Kharkiv region.

This series, titled Executed Free Speech, is created as part of a project Drawing Ukrainian And International Audience’s Attention To Serious Violations Of Human Rights And Crimes Against Journalists And Mass Media By The Russian Federation, which is performed by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, with support from the Swedish non-profit organization Civil Rights Defenders.

JOURNALISTS ARE IMPORTANT. Stories of Life and Work in Conditions of War is a cycle of materials prepared by the team of the NUJU with the support of the Swedish human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

#CRD

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post