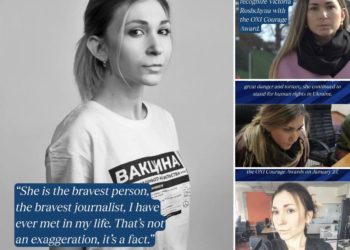

We spoke with international media producer Sofiya Kochmar about the importance of covering terrible war events, communication with people, empathy, one’s own psychological stability and recovery.

Today, many films, stories, and projects covering the bloodshed in Ukraine have entered the Ukrainian and foreign media space. Journalists and producers show the whole world what the terrorist country is doing and how it is horribly destroying the Ukrainian people. One of the most important functions of modern journalism and cinematography is to tell and document everything, not to leave anyone indifferent, and to attract the attention of the world. That’s what journalists do today.

Sofiya Kochmar helped create (was a producer of) the film called I Call Him By Name for the London BBC; The Lost Souls of Bucha for the socio-political TV show 60 Minutes on the American CBS TV channel; a documentary about the deportation of children for the French BFM TV; also talked about women’s captivity and the survival of Ukrainians during the blackout. Sofiya became the winner of the Emmy Award for the documentary Lost Souls.

– Ms. Sofiya, before the start of the full-scale invasion, you worked in Ukrainian journalism as a television reporter, prepared materials for the Ukrayinska Pravda online publication, and had many different projects. How did you decide to write and film about the bloody events in Bucha and tell the world about the horrors of the Russian-Ukrainian war because it is difficult psychologically?

– Actually, I don’t think that talking about Bucha is psychologically difficult, and I never thought that I wouldn’t go there because of fear. It is very, very good to work there in the sense that you are doing the work you have been preparing for all your life. I understood that this is a very important work dedicated to my people. I really wanted to go there and quickly decided that I would go.

I went to the monastery for a week in silence, thinking about where I should be now and what I should do. The first thing I saw in the information space when I left the monastery was the truth about Bucha, and it was a sign that I should be there. If you are a Ukrainian journalist and are afraid to go to Bucha, then why did you start working in journalism in the first place?

– During the filming of the movie I Call Him By His Name, you spent 50 days in the recently liberated city as a researcher; you spent two months in Bucha for the filming of the documentary called Lost Souls. What was the most difficult during that time?

– I worked on the identification of the bodies of the killed in Bucha and the creation of a single list of the killed in the mass grave under the church. I don’t think there was anything categorically very difficult. It was very difficult to show our war reality to people who are outside this reality, that is, to foreign audiences and colleagues from abroad. It wasn’t easy to connect these two realities: ours and theirs.

– Do you have a main rule or guideline that you always use when preparing projects on difficult but important topics?

– I don’t think I have any single rule to continue working on difficult but important topics. They have become so normal to me that I don’t know how it is to work with anything else.

My main rule is to be in the resource. You can’t go to people who have lost their main resource in life without a resource of my own, and that’s also what I learned after the invasion. I will not be able to do the following projects if I do not take care of my own resource.

I’m still just learning how to do it.

How do others do it? Everyone has to find their own way. I find it in communication with God, with my own child, in conversations with people I love. When I worked in Bucha, I had special hours of communication with colleagues or friends whom I had not seen for a long time. We were talking about something that had nothing to do with war, Bucha, or deaths. We were just talking about life. And this was my very important help to stay in the resource.

– The heroes of your journalistic materials are ordinary people who have suffered. It’s hard for people to talk about all the things they’ve been through. How do you find people ready to share their stories with you?

– To find heroes, you have to walk towards them. I was taught this at the Faculty of Journalism at Lviv University. A good journalist earns money with their feet! This rule works very well in cases like Bucha.

You simply go to the place of events, live among people, go where they go, and that’s how you find them. You talk a lot with people, listen a lot, and that’s exactly how I found my heroes. I worked off the record.

I also have another rule – I approach people as a person, not as a journalist. Of course, I warn them that I have come to them as a media worker, but I listen to them and talk to them not at all in a journalistic way but as a neighbor or relative would talk to them. This humanity and empathy help me find people ready to share their stories with me.

– How do you communicate with people so as not to hurt them again?

– Actually, I don’t think that journalists hurt people. People’s feelings can be hurt by any person, but not necessarily a journalist. It is not your profession that hurts a person but what kind of person you are. If you are an empathetic person, open to people, and one who knows how to feel human pain, then you do not necessarily hurt your interlocutor, even when you talk about a difficult topic for him.

There are, of course, cases when you can injure yourself unintentionally. For example, if you didn’t know that it could hurt, that it could trigger, then you don’t have to blame yourself so much. You just didn’t know it could backfire like that.

I communicate with people several times. I don’t work through asking them to tell me the perfect phrase in 15 seconds, and I’ll go and show it on air. I spend a lot of time with these people, helping them bring packages from the store, investing in our relationship with them, and it helps not to traumatize them during conversations.

– How do you find the golden mean between empathy and a certain detachment because it is very difficult to take on all human pain?

– I am not a person looking for detachment. Perhaps because I work with international colleagues, and they are already detached from the material, they are the ones to be responsible for this. I tried to be detached once because I thought it would hurt me too much to get too caught up in the story. It turns out that creating a false detachment is more traumatic for me than being who I am. If I am in a resource and have something to share with people who are in trauma, I do that. Unfortunately, the traumas I’m working with are stronger than any detachment I can picture for myself and somehow create. Detachment doesn’t work for me.

– Preparing materials about all these terrible events is psychologically difficult for the journalists and producers themselves. How do you maintain your own psychological stability and recover?

– I hope that I still keep it. Now, I started working less. At the beginning of the invasion, I worked for months, had three or five days off, and went to the next task. Now I work much less.

I come up with some standalone dates for my rest. I’ve also discovered the world of SPA and baths for myself. I highly recommend it to colleagues. The military taught me this. The bath helps to relax the body. If you don’t try to relax your head, if you don’t have a relaxed body, it won’t help you.

I also meditate, and I have a psychotherapist. People I love help me a lot. It is very important to get rid of people in your life who take away your resource – this also helps to maintain psychological stability.

If you work as a trauma journalist, the characters of your stories still take away your resource, but it’s your choice to work with these people. So, if I go back to my real life, I get rid of the people who are taking away my resource in real life. These are people who use me, for example.

I clean up the circle of my communication as much as possible in reality, that is, not in work, but in reality. This is truly my big recommendation.

It would help if you were with people who add to your resource, not take it away.

– What are the three main pieces of advice you could give to a modern journalist?

– First of all, advice for a young journalist – think carefully about whether you really want to work in journalism, why you need it. If you come to build a career, to establish your own ambitions, then, unfortunately, journalism is not the profession in which you can realize such ambitions. These ambitions will cost you a lot of health and time. Now is not the kind of journalism you should go into for your own ambitions.

Three main instructions for journalists who already work:

- Fact checking

The first and very important thing is to take care of fact-checking. Build your own information verification skills. All information must be well verified. Do not share information that has not been fully verified. Our primary goal is truthfulness, not speed. We do not work for speed but for truthfulness and accuracy.

- Information campaigns during other wars

I highly recommend reading about the various information campaigns during other wars, about how Mossad, and Tzahal work. It is worth reading about various special information operations as we have been participating in similar events for two years already.

- Life outside journalism

Live a life outside of journalism! Build families, have friends, and invest in your mental health in the same way as in work, both in terms of time and money. Invest in your family and friends because who you are outside of work is very visible in your work!

Call the unified Lviv-Chernivtsi Journalists’ Solidarity Center at 097 907 9702 (Nataliya Voitovych, the coordinator of the Lviv JSC, Volodymyr Bober – assistant). The Center’s address is 5 Solomiyi Krushelnytskoyi Street.

ABOUT JSC

The Journalists’ Solidarity Centers is an initiative of the NUJU implemented with the support of the International and European Federations of Journalists and UNESCO. The initiative is designated to help media representatives working in Ukraine during the war. The Centers operate in Kyiv, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Chernivtsi, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro and provide journalists with organizational, technical, legal, psychological, and other types of assistance.

ABOUT UNESCO

UNESCO is the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. It contributes to peace and security by promoting international cooperation in education, sciences, culture, communication, and information. UNESCO promotes knowledge sharing and the free flow of ideas to accelerate mutual understanding. It is the coordinator of the UN Action Plan on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, which aims to create a free and safe environment for journalists and media workers, thus strengthening peace, democracy, and sustainable development worldwide. UNESCO is working closely with its partner organizations in Ukraine to provide support to journalists on the ground.

The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this digest do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area or its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this digest and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit to the organization.

Alina Shtempel

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post