In the first hours of russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when most Ukrainians were still trying to grasp the reality of the first explosions, the russian invaders already had a clear plan to capture the most influential information resources of the occupied territories.

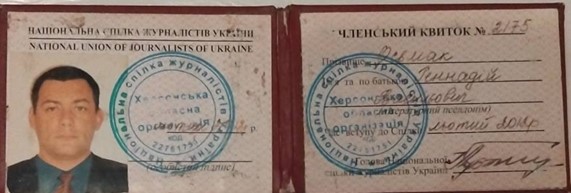

One of their goals was the website Novyi Vizyt [New Visit], an independent publication in Henichesk, Kherson Region, a strategically important city on the administrative border with occupied Crimea. This website, for many years was managed by an experienced journalist, a member of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU), Hennadii Osmak.

Osmak headed local state television for a long time and thus opened his own news portal, which quickly became one of the most popular in the region. Novyi Vizyt was the second-ranked edition of the Kherson Region, attracting a huge audience, especially when covering events on the administrative border with Crimea.

“Local media were popular in the Henichesk Community,” Kherson-based journalist Oleh Baturin told the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine in a comment. “Novyi Vizyt was among the most popular. The site was loved for its straightforwardness. The uncompromising position of the publication caused the appearance of enemies of Hennadii Osmak in the community. I know some of these people, and I am convinced that the criticism from Osmak was quite fair. Later, after the invasion of the russians, these odious persons were given positions of influence, and their hands were freed for revenge.”

The site, which actively covered the life of the region, in particular, numerous actions of Crimean Tatar organizations, military exercises, etc., was popular even among russian readers, which testified to its significant influence in the information space.

Even long before the full-scale invasion, Osmak‘s website regularly suffered from powerful hacker attacks, especially during local elections. Russian structures tried to silence the independent voice of the journalist since 2014. Therefore, it is not surprising that already in the morning of February 24, 2022, the occupiers blocked access to the site.

As a source from the Kherson Region, who asked to remain anonymous, told the NUJU, two days after the beginning of the invasion, the occupiers arrived at Osmak with an ultimatum: either cooperate with the “new government” or hand over the electronic keys to the site. Osmak did not go to the collaboration. Given the undisguised threats of the occupiers, Hennadii Osmak agreed to give the occupiers technical access to the site but publicly distanced himself on Facebook from any content that could appear on the seized resource. However, it is true that soon the site was completely closed.

For a year and a half, Osmak tried to remain inconspicuous in occupied Henichesk. He earned his living by taxiing. He could not leave as the occupiers put him on the list of persons who were forbidden to leave the city. But the invaders did not forget about his previous journalistic activities. They carefully analyzed the archive of his publications, especially focusing on materials about Crimean Tatar actions, military exercises, and other pro-Ukrainian events.

The consequences were cruel. In March 2024, russian security forces arrested Osmak, and on July 23, he was put on the “terrorist” list. The occupiers subjected him to brutal torture despite serious health problems, diabetes, and a recent operation. After the torture, his condition deteriorated significantly.

In the end, the occupation “court” sent the journalist behind bars for three and a half years. The accusations were directly related to his journalistic activities – covering the activities of Crimean Tatar organizations, military exercises, etc. As reported by the Rayon.Henichesk website, referring to the occupation sources of information, Hennadii Osmak was accused of allegedly “joining the armed formation Crimean Tatar Volunteer Battalion named after Noman Chelebidzhikhan, which is recognized as a terrorist organization and banned on the territory of the russian federation.” Russian prosecutors claimed that Osmak allegedly provided the “battalion” with construction materials, supplied food, etc.

“It is clear to all local residents who know Osmak that this is complete nonsense. With such a verdict, the occupiers are simply taking revenge on Hennadii for his civil position,” writes Henichesk journalist Danylo Azovskyi.

On the conviction of colleagues, the russian “court” interpreted Osmak‘s media activities as cooperation with organizations banned in russia. His status as an independent journalist who was doing his job, covering public events, was completely ignored.

“Hennadii Osmak proves with his whole life what the true independence of a journalist means,” assures the Kherson journalist Yevheniya Virlych. “Having started working as an operator in the 1990s, he went through a rather difficult and interesting path, in which it is difficult to find even a single hint of involvement, “marketability” or something else. No matter how many elections and how many different powers, he always knew and knew how to remain a human being, a professional, and not just neutral: independent. Because independence and neutrality are completely different things.”

But, the journalist adds, when the russians want to find a reason to attribute a person’s participation in ephemeral “groups” and other delusions, they will do it. They don’t need evidence; they make it up. They will even find “witnesses” who will “confirm” everything.

“Hennadii Osmak‘s case is a vivid example of the danger faced by journalists in the occupied territories and the methods by which the russian authorities try to suppress independent voices,” noted Sergiy Tomilenko, the President of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine. “But the fate of Osmak is a story not only about a personal tragedy but also about the strength of spirit and indomitability of Ukrainian journalists who, even under the threat of torture and imprisonment, refuse to become tools of enemy propaganda.”

Currently, about thirty Ukrainian journalists are being held captive by the russians. The NUJU expresses its solidarity with every media worker held captive by the occupiers and makes efforts to return each of them home to their families and their favorite jobs.

Created as part of the project “Raising awareness among target groups in Ukraine and abroad about Russian war crimes against journalists in 2024 and increasing public pressure for the release of captured journalists”, which is implemented by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine with support of the Swedish non-profit human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

NUJU Information Service

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post