The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU) is a long-standing partner of the Belarusian Association of Journalists, which is in strict opposition to the regime of Alexander Lukashenko and is forced to work outside Belarus. “The NUJU are our friends” were the words the deputy head of BAJ, Barys Garetski, began the interview with the President of the NUJU, Sergiy Tomilenko.

“We are proud of our friendship and partnership with the independent, proud Belarusian Association of Journalists,” Sergiy Tomilenko said in response. “We are very sorry for the fate of independent Belarusian journalists who, unfortunately, are subjected to repression in their native country and who had to become refugees.”

The President of the NUJU also noted that Ukrainian media workers are also experiencing extremely difficult times and that every media outlet is currently in a risk zone. Unfortunately, since the beginning of the full-scale russian aggression in Ukraine, 73 media workers have been killed, including 16 while performing their professional duties.

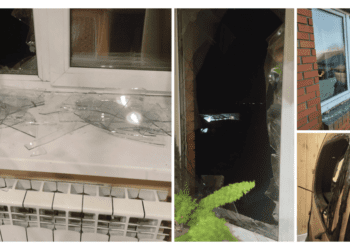

“We clearly see that journalists are the targets of the russian military offensive. Today, recommendations are coming from the front for journalists to take body armor without the PRESS mark on business trips to dangerous areas. russians do not follow any conventions. They hit newsrooms and detained journalists in the occupied territories, forcing them either to cooperate with the occupiers or to keep quiet. The absolute majority of Ukrainian journalists do not cooperate with the enemy. At the same time, in the conditions of russian occupation, no open independent journalistic activity is possible,” Sergiy Tomilenko stressed. “So, journalists from the occupied territories must either become forced migrants or leave the profession and “lie down.”

Unfortunately, the russian union of journalists has turned into a structure that, in fact, “helps the Kremlin fight.” It formed its regional “departments” in the occupied territories of Ukraine. Therefore, the NUJU made efforts to subject this organization to a boycott at the international level.

It is not easy for journalists to live and work in a free territory, both because of the russian shelling of Ukrainian cities and because of the economic crisis caused by the war.

“Some journalists and editors are running out of stamina and enthusiasm because the editorial “conveyor” needs economic resources and communication with the audience. Therefore, although the component related to professionalism, talent, and diligence is high, there are still questions about how to survive in the conditions of the ongoing war,” Sergiy Tomilenko noted. “We see changes in the media landscape. On the one hand, new media projects and high-profile investigations appear, but they become possible only thanks to international grant programs. On the other hand, local, regional journalistic teams – both in front-line and conditionally peaceful regions – are experiencing crisis phenomena. Fortunately, thanks to international solidarity, there are programs under which a large number of editorial offices also receive assistance. Today, it is very important, but it is impossible to predict what will happen in the future.”

In addition, local print media suffer from the conflicting national postal operator Ukrposhta, which has not established partnership relations with the publishing industry. This leads to the fact that post offices are closed, mail carriers are fired en masse, and newspapers are lost. At the same time, tariffs for postal services are increasing.

As a result of all this, a third of Ukraine’s printed editions were closed. Journalists unable to find work in other newsrooms either work as information volunteers on social networks or were forced to leave the profession.

“The editors, who consider their publication as a mission and are eager to develop it, hold on at the cost of incredible efforts,” says Sergiy Tomilenko. “Yes, the newspaper in Novhorod-Siverskyi divides the salary of one journalist by four. At the same time, the city, located near the russian border, is under constant shelling.”

At the same time, Sergiy Tomilenko emphasized the new role of print media in the front-line and de-occupied territories during the war. In conditions where the occupiers are destroying the infrastructure, the opportunities to spread information through television, radio, and the Internet are significantly reduced. Therefore, newspapers become the only type of media available to the broad masses of the population. The NUJU identified as one of its priorities the promotion and revival of front-line printed publications. Just a few days ago, the 29th newspaper was published, the printing of which was restored with the help of the NUJU and its partners – Holos Huliaipillia [Voice of Huliaipole].

“A unique example is the Bakhmut Town newspaper Vpered, which we managed to revive last fall. Volunteers took her to Bakhmut, then, when it got really “hot” there, the military did it. This newspaper saved thousands of lives by explaining to the people who were hiding in Bakhmut basements the possibility of evacuation from the city engulfed in war and flames. People made the right decisions by trusting their native newspaper,” said Sergiy Tomilenko. “Now, the newspaper’s publishing is underway. It is distributed among the displaced Bakhmut residents. It launched the project The Town Of Our, collecting the opinions of Bakhmut residents, what their city should be after the de-occupation and the end of the war.”

Sergiy Tomilenko emphasized that international support helps Ukrainian media to survive and develop. The NUJU participates in powerful forums, and everywhere, the support of Ukraine and Ukrainian journalists is unequivocal. The President of the NUJU thanked foreign journalists for their work, who inform the world about the events of the russian-Ukrainian war and thus contribute to the support of Ukraine and Ukrainian journalism.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, the NUJU itself has moved to extraordinary working conditions. They gave recommendations to colleagues on how to behave in the event of a power outage and where and how to evacuate. It contacted colleagues on the front-line and occupied territories. In the first days of the large-scale war, the NUJU deployed two relocated offices – in Ivano-Frankivsk and Chernivtsi. It also received calls to the hotline from colleagues who needed help keeping in touch with foreign journalistic and humanitarian organizations.

International partners proposed to create a large shelter in the western regions of Ukraine – a refuge for journalists forced to leave their homes. But the Union decided instead to create a network of Journalists’ Solidarity Centers (JSC) – small offices that receive calls and messages from colleagues who have suffered from russian aggression and help them. Initially, three such centers were created – in Ivano-Frankivsk, Chernivtsi, and Lviv. Therefore, centers in Kyiv, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro were added to them. With the support of the International Federation of Journalists, UNESCO, and other international partners of NUJU, the centers of journalistic solidarity are equipped with computer equipment, protective equipment for journalists who need it, electric generators, Starlinks, and power banks. The JSCs support journalists materially, help them find work and housing, and conduct the necessary training sessions and webinars.

“Our duty is to find resources that we can share with those who need them the most, who suffered from the war,” said Sergiy Tomilenko. “We are convinced that in a free Ukraine, for which we are all fighting, free journalists and free media, which are valuable to us, should work.”

NUJU Information Service

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post