During her stay in Lutsk in late 2023, Lina Kushch, the First Secretary of the National NUJU (NUJU), in addition to holding a number of interesting meetings with colleagues from the Volyn Region, gave a lengthy interview to Public Interactive Television. Answering the questions of her colleagues, she spoke about what the Ukrainian mass media in all regions of our country are experiencing today and what problems the NUJU is primarily concerned with.

Lina Kushch spoke about the following:

The regions are different, but the problems are similar

The NUJU is the largest journalistic organization in Ukraine, uniting 18,000 members. And now we can see how the needs of journalists are changing during these two years of the full-scale war. If we may say that in the first days and weeks after the large-scale invasion, security was of primary necessity, but now, the biggest need is in recovering from the forced break in activity and continuing the work of journalists. Psychological support is needed as the heavy load carried by our colleagues is very noticeable.

Despite the fact that each region in Ukraine has its characteristics, there is much in common in the work of the media. The NUJU conducted a study of the needs of local media in the de-occupied and front-line territories, and we found out that the data of this analysis are characteristic of almost every region.

In all regions, more than 80% of newsrooms lost advertisers due to the war, and 60% of newsrooms said they did not have enough money to pay salaries. According to our data, every fourth journalist in the regions often works without pay at all, and another half of media workers work with reduced salaries. Despite the fact that since the beginning of the large-scale invasion, the workload of local media workers has increased.

We keep in touch with many local media, including local TV and radio companies. And they noted that the number of views and the number of visitors increased very sharply – in a geometric progression. That is, at a time when people are in a situation of uncertainty and anxiety, they try to turn to proven sources of information. And people see professional journalists and professional media as such sources of information.

We work in close partnership with international organizations

The economic consequences of the full-scale war in Ukraine are very unfavorable for Ukrainian journalists and the Ukrainian media, and we are working to solve these problems in the NUJU.

Together with our international partners, in 2022, we organized a network of Journalists’ Solidarity Centers (JSC), where journalists can rent protective equipment, receive advice, attend safety training, and get legal and psychological assistance. The activities of the JSC are supported by the European Federation of Journalists, the International Federation of Journalists, and UNESCO.

We are also engaging a number of other partners so that Ukrainian professional journalists can work and continue to inform Ukrainian society. At the same time, we understand well that often, the local media is the only source of verified information, and if there is no local media, this vacuum will be filled with hostile propaganda.

- During the large-scale war, people rushed to the mass media for information, but later, they switched to various Telegram channels, which often publish unverified information. And now it is a huge problem in society. At the same time, the media in the Volyn Region still have a problem with obtaining information from official sources: journalists often complain about the belated reaction of representatives of local authorities to events or that authorities do not contact them at all. How to deal with it?

This is a real problem characteristic not only of the Volyn Region. On the one hand, we understand that martial law implies certain limitations in informing the general public. For example, journalists should not publicize the location of certain objects, the consequences of enemy missile attacks in relation to the area, etc. And that’s understandable. But it is impossible to justify the cases when local authorities are closed to journalists (for example, under the pretext of martial law, journalists are not allowed to attend council sessions).”

Today, the doors of the Verkhovna Rada are also closed to journalists: journalists cannot promptly take comments from parliamentarians before voting, after voting, or receive comments on important events. It is also not possible to get to the meeting of the Cabinet of Ministers in order to get the latest comments from government officials. The same is often seen at the level of local authorities.

This is unacceptable; it is a direct violation of the rights of journalists and an unjustified restriction of freedom of speech. After all, the role of journalists consists of providing publicity to important information and encouraging authorities to be transparent in their decisions. When the government is closed, it gives grounds for abuses and corruption schemes; it grounds mistrust of our government. At the same time, this situation encourages ordinary citizens to trust some unofficial information resources they receive distorted information from dubious sources.

- I would like to know your opinion regarding the Unified Telethon. Hasn’t it exhausted itself? Perhaps it should be abandoned or at least changed in its format?

I believe that the Unified Telethon has exhausted itself two months after its start. After that, it would be worthwhile to provide an opportunity for television companies to develop, conduct their broadcasts, and give people a more diverse picture of events and a more versatile discussion of certain topics.

It is necessary to create such conditions so that different television companies can conduct their independent editorial policy and present alternative opinions about events.

Ukraine is a democratic state. We can freely discuss all issues that concern society and find common solutions, and this is what distinguishes us from dictatorial regimes. And it is not normal when in the Unified Telethon, we see, for example, when discussing some topics that concern society, only one point of view. And this is the government’s point of view.

In the first weeks of the large-scale invasion, the Unified Telethon was valuable in that it was attended by top officials of the highest echelons of power, and it was possible to get first-hand information and comments about the events that were taking place. Today, we see that the program features people who do not shape state policy but simply voice power’s messages.

The NUJU has repeatedly drawn attention to the fact that the authorities should create the basis of independence for all media in Ukraine, not only for state media and those working in the telethon. All Ukrainian media must be financially independent from big politics and big business.

Now, only thanks to international partners, NUJU has certain funds to support newspapers from the front-line and de-occupied territories for certain social benefits. We understand that during the full-scale war, most of the state budget of Ukraine is spent on the needs of the army. And yet, in our opinion, the Ukrainian authorities, at their level, together with international partners, even in the conditions of this brutal war, should form a fund to support Ukrainian media so that any media working in the legal field and meeting certain criteria could apply to this fund.

It is impossible to talk about the recovery of Ukraine without talking about the recovery of the media. If, for example, we are talking about international partners taking over the restoration of the Odesa, Mykolayiv, and Kherson Regions, and where does this program say about the restoration of media in those regions? If we are talking about the restoration of Bucha or Hostomel, where in this program is the restoration of local media, which were also damaged or destroyed?

- In Ukraine, the new Law On Media came into force, and in connection with this, many changes were made in the work of the media. In particular, from now on, the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council of Ukraine can issue licenses or terminate the activities of not only television and radio companies but also those of the print media. What do you think?

Regarding the implementation of the Media Law, the NUJU has repeatedly emphasized that its implementation may have negative consequences. And not only because of the broad possibilities given to the National Council (for example, to apply prescriptions, fines, and other forms of sanctions) but at least because this law is very large in scope – it has 300 pages.

The Law On Media is complex, and not every newsroom (especially if it is a small newsroom of a local media) has lawyers to professionally study the law and think about how to implement it or how to prevent possible violations will professionally meet the requests of the National Council.

After the entry into force of this Law On Media, the status of a journalist has changed, for example. If previously online media journalists who were not registered but actually carried out journalistic activities had the right to have a journalistic status as well as to the protection of journalists, now, according to this law, journalists of unregistered online media are not actually journalists.

It turns out that, on the one hand, the law does not provide that online media must necessarily be registered; on the other hand, journalists were not protected. This is a step backward in the protection of journalists’ rights and one of the negative features of the law. We, as the NUJU, closely monitor its implementation, participate in the discussion and analysis of by-laws, and in some cases, we have already provided our comments.

- How many NUJU members were mobilized during the large-scale war and took weapons instead of a pen or a microphone?

According to a survey conducted in 2022, 15% of newsrooms have on their staff journalists who have been mobilized to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) or joined the Territorial Defense forces. And according to our estimates for 2023, this figure will be at least twice as large. Every third Ukrainian newsroom has on its staff journalists who have gone to the front. The number includes many volunteers. There are newsrooms whose editors stood up to defend Ukraine at the front.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine, 75 journalists have been killed. Sixteen of them were Ukrainian and foreign journalists killed while performing their professional duties in the fighting zone. Ten more journalists were civilian victims who were killed in shelling at their homes and outside. All the rest were volunteer journalists and those mobilized to the ranks of the AFU. We remember each of them. If it weren’t for the war, they would be alive; they would be around, working together with us.

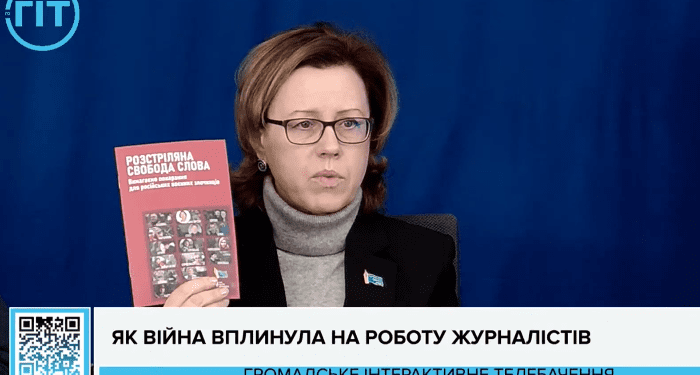

The NUJU prepared and printed the booklet Executed Free Speech. It included the stories of journalists killed since the beginning of the full-scale russian invasion of Ukraine and the stories of media workers who ended up in russian captivity. There are also cases of destruction of property and editorial buildings and persecution of Crimean Tatar journalists on the temporarily occupied peninsula.

- Is there any social protection for reporters working in the combat zone and the same for journalists who have been mobilized?

With regard to mobilized journalists, they, as well as all military personnel of the AFU, are subject to the relevant Ukrainian legislation.

As for professional work in the war zone, our Ukrainian journalists, unlike their foreign colleagues who work at the front, are practically not protected. On the one hand, there is legislation that obliges the employer to insure an employee who is sent on a business trip to a war zone on the assignment of the editors. On the other hand, there is no mechanism for such insurance because no insurance company insures Ukrainian journalists living in Ukraine and working in the war zone.

For comparison, the insurance of Swedish journalists for one week of work in Ukraine costs EUR 6,000, which is quite expensive for Swedes. I also spoke with one of the German journalists – a TV presenter who periodically works in Ukraine. According to him, one trip to Ukraine, together with transport, accommodation, car rental leading to the front line, etc., costs EUR 10,000.

There are certain donor programs where a journalist can get insurance for three or five days. But these programs, for example, cannot be used by Ukrainian journalists who live and work in front-line and de-occupied territories because they spend a very long time in the war zone, and it would be very expensive. Therefore, journalists on the front-line and de-occupied territories in the border regions constantly under fire are practically not protected. And the threat to life there is constant.

No matter how scary it sounds, our colleagues living and working in the risk zone are already used to this. For example, a journalist from Velyka Pysarivka, Sumy Region, said that when the shelling began, they did not even go to shelter and did not stop working on the material. They simply move the chairs and sit at the other end of the table, further from the window.

- Do you have information about those journalists who remained in the occupied territories?

Unfortunately, in the occupied territories, the russian occupiers arrest and hold journalists captive. These are UNIAN journalist Dmytro Khyliuk, who is in a russian prison, Iryna Levchenko, and several of her colleagues from Melitopol, who worked for the RIA Melitopol website and were detained at the end of August 2023. Journalist Viktoriya Roshchyna has disappeared, and we do not know her whereabouts. There are many illegally detained and imprisoned journalists and public journalists in Crimea.

The occupiers resort to various forms of pressure, extract the necessary testimony from people, and then arrange for the detention to be videotaped, allegedly in compliance with all procedures, and may even invite a lawyer. But people are already so broken by that moment that they are ready to discredit themselves and say on camera that they are terrorists, spies, traitors.

The problem is that we do not have a procedure for the release of civilian prisoners. Journalists are not combatants, and under all conventions, they cannot be put onto exchange lists. The lack of procedure and international pressure on the aggressor country in this matter prevented the release of our colleagues.

- Is it possible to somehow help with this?

The NUJU is a partner of a number of organizations that can submit cases of the death or capture of journalists to the platform of the Council of Europe on the Safety of Journalists. This is an effective mechanism that draws attention to these cases at the level of the Council of Europe.

Of course, russia ignores all the appeals of the Council of Europe and all requests to provide comments to take measures to stop the murders and capture of journalists. At the same time, it is important that absolutely all these crimes are recorded. We documented on video more than 100 stories of journalists who became victims or eyewitnesses of russian war crimes, translated these video stories into English, and promote them on international platforms.

We call on our international partners to spread our stories about how Ukrainian journalists are held captive, how they were forced to evacuate and how their homes were destroyed, how Ukrainian journalists were deprived of their jobs as a result of russian aggression, etc. These stories will not go outdated unless they [the enemy] are held accountable for the crimes and the punishment for those guilty of committing these war crimes is carried out.

Olha Voitsekhivska, Journalist of Ukraine.

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post