Olha Musafirova is an own Ukrainian correspondent working with the foreign publication Novaya Gazeta. Europe. It was created after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion. The newspaper covers stories about the Russian-Ukrainian war without fakes and propaganda. The publication is mainly aimed at a European audience, particularly a Russian-speaking one. The war affected not only the professional life of the media woman: her son joined the ranks of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU) to defend Ukraine. At the same time, Olha maintains her “front,” the informational one. Olha Musafirova met on the first day of the war at home, her Kyiv apartment.

“I knew that under any circumstances, I would stay in Kyiv and continue to work as a journalist”

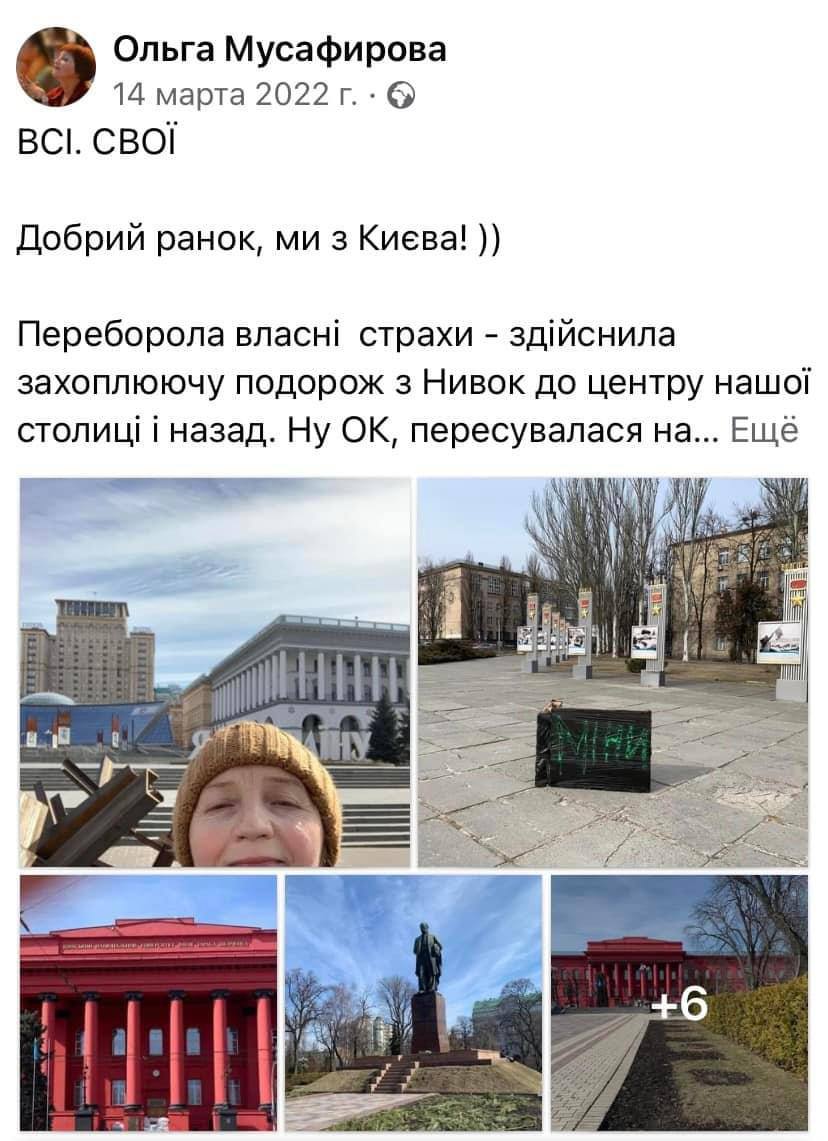

“On February 24, like the previous days and months, when I did not go on a business trip, I was in Kyiv, at home,” the media woman says. “I felt before that a full-scale war was coming. I even re-watched several broadcasts of talk shows on national channels to where I was invited and made sure that I spoke about them. The only thing is the very format of the war, which we all talked about (when I say all, I mean media people and political scientists): most of us had the conviction that a great war was inevitable and that Russia would not surrender just like that, but such, as it turns out, we didn’t expect it (at least I didn’t). Although I still chastise myself for one broadcast, where, sitting in the studio, I threw the following phrase: “Well, now we will live like in Israel: holding a machine gun with one hand and rocking a cradle with a small child with the other.” Now I would slap myself for that because you can’t say beautiful, loud, but empty phrases about war. It is easy to say, but it is impossible to realize yourself in this situation in real life. But then the audience clapped. It seemed to everyone that it was very aptly said. So, on February 22, 23, and 24, I packed an emergency suitcase; well, you can’t call it a suitcase, it was a shoulder bag, which I was always packing, sometimes transferring something in there. A laptop, rechargeable batteries, drinking water, money, and documents. Until I realized: why, in fact, am I doing this? I am not going to go anywhere from Kyiv. I no longer have small children, as they have grown up, and unfortunately, I no longer have my parents either. That is, all people in the family are adults. I knew that under any circumstances, I would stay in Kyiv and continue to work as a journalist.”

On the night of February 24, Olha did not dream of anything. She couldn’t close her eyes. I flipped through the news with anxiety, watched Putin’s speech, and then… the explosions began.

“I heard a deafening “boom” several times outside my windows. Because our house is not located in an industrial zone, but not far from us is the Antonov factory, those infrastructure facilities, which, as it turns out, they like to strike so much. There were three or four loud explosions, and only then the air raid alert siren went off,” Olha continued. “I went to my son’s bedroom, put my hand on his shoulder, and said: “Dima, the war has started.” He got up quickly, and in a few hours, we agreed on a further action plan. The son enrolled in the armed forces; now he is in the AFU.”

The mother had no option of “not supporting her son’s decision.” Moreover, he once told her such a crucial phrase: “I grew up on your news materials.”

The mother had no option of “not supporting her son’s decision.” Moreover, he once told her such a crucial phrase: “I grew up on your news materials.”

“Of course, I’m afraid, but how can I not be afraid? To a certain extent, I occasionally stuff my head with more work so that panic thoughts disappear. But he is a strong, prudent, intelligent guy. He continues to read my news materials; I send them to him when there is a connection. In addition to questions about “have you eaten?” and “are you safe?” I send my reports from Odesa, Kherson, Kramatorsk… His opinion is critical to me,” says our interlocutor.

“And I felt a certain superiority in those first minutes: why are you crying? It’s me who is being bombed”

Half an hour after the first explosions, Olha got a call from Novaya Gazeta, whose newsroom was then in Moscow.

“This liberal publication provides anti-war and anti-Putin views. The editor of the international department called me: he was crying. He said, “Olia, we couldn’t stop it.” And in those first minutes, I even felt a certain arrogance: why are you crying? It is me they are bombing now! And I even quietly calmed him down. Like, now the international community will rise, and, of course, it’s terrible; there will be human losses… But I had a feeling at the time that the madness would not last long, and Putin already had a few days left after what he did. In another 15 minutes, the editors asked me to go live. I took a five-minute time-out, brushed my hair, and dressed. We have two balconies: one unglazed, the one that opens into the yard, and the other glazed, the one facing the street, where the flag of Ukraine hangs. And from this balcony, you can see Peremohy Avenue and the office building of the Antonov Plant. I stood on the little stool to be closer to the flag because it hung high. I said something there; I don’t remember what. There was adrenaline, but there was no awareness that it could touch me, kill me. Colleagues then said they were amazed because, in this video, black smoke was rising in the background. That is, an enemy missile hit something somewhere very close,” says journalist Musafirova, who realized what really happened after that broadcast about an hour later. Then, the media woman says she had a little panic attack.

“Legs are shaking, lips are shaking, and there is a flood of phone calls and invitations to interviews. And I began to refuse; I felt that my psychological resource was exhausted, and I would not be able to say more than what I told the readers and listeners of our publication. The least of all, despite the fear, I wanted to be in the role of a victim, sitting covered with my hands and crying out due to the fright. After a few hours, we corresponded with the editors in the work chat; I said I would not go anywhere from Kyiv. And where is there to go? The family is here; my men are doing what men in Ukraine are supposed to do during the war. I will not go anywhere alone. Moreover, we have a cat. And he doesn’t like to drive. I knew I would have to work. There was no understanding of how to work in such a situation. Although in 2006, I worked in Israel when there was another escalation of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. In 2008, I was in the war in Georgia, but, you know, these are completely different things; I realized it only now. For a journalist, it is one thing to work in a war, go there on a business trip and writing materials, and then return home to a quiet, peaceful country, and it is a completely different story to live and work in a war.”

“Without a doubt, I wanted to communicate with people who survived the occupation”

For almost a year of the war, Olha Musafirova prepared many reports from various settlements, particularly those that had just been liberated. Although, she does not consider such business trips as heroism.

“Since, unfortunately, I do not have my transport, any trip to the newly liberated area is connected with solving logistical issues: how to get there? Many journalists travel with volunteers. And journalists perform two functions “write material and help volunteers. Likewise, I went with the volunteer charitable foundation called Ants. First, I came and asked how I could be useful, transferred certain funds to their account, and helped pack things. And so, during joint work, I got to know them, learned what kind of people they are, how they become volunteers, and how they are not afraid to travel to dangerous areas. After all, this is not a very simple story, considering the road: bridges were destroyed, and roadsides were mined. Without a doubt, I wanted to talk to people who lived there during the occupation; with the help of volunteers, such things are done much easier,” the journalist continues.

“My status has not changed, but the responsibility has grown exponentially”

The war in Ukraine changed the work of the publication where the media woman worked.

“Some of the colleagues who already left Russia for Europe in March started working on creating a new, separate, legally separate publication of Novaya Gazeta. Europe,” says Olha Musafirova. “It is registered in Latvia and issued for the European Community. Comes out in Russian. There is a website. We cannot translate all materials into English and German, but the most significant materials, materials from Ukraine, are translated so that the European reader can learn the truth. And, of course, so that the Russian-speaking community (I avoid saying “Russians,” but I am talking about those people in Europe who read in Russian and understand it) could learn from this publication what is happening in Ukraine and what is happening in Russia. From an ethical point of view, I am not sure that it will be okay if I still say that my whole previous life was like a preparation for working in the current conditions. Am I able to work, or will I go and say that this is too much of a test? I decided that I had to endure it. However, it is not easy, of course. Now my status is own Ukrainian correspondent working for a foreign publication. And now my status is unchanged, but the responsibility has grown exponentially.”

“There are no things that may distract the reader’s attention, entertain or provide any unclear statements”

“There are no things that may distract the reader’s attention, entertain or provide any unclear statements”

With the beginning of the full-scale war, the journalist’s close and professional environment did not actually change. But the people I can now call acquaintances have been ousted from the close circle.

“In general, I make very high demands on the people who surround me, whether in a close environment or a professional environment, so I am not waiting for a war or similar changes to say goodbye to people,” says the journalist. “This is a well-selected society. However, we maintain less frequent relations with those who remained in Moscow. Why? You know, conscientious and intelligent people find it extremely difficult and painful even to ask me something. Asking for forgiveness all the time is not a dialogue. I know they did their best. Now the young part of the editorial staff, which has left and is now scattered around Europe, is trying to do the same. The team publishes a printed version with the most resonant materials, and somewhere 90-95% of the newspaper is materials about Ukraine and its surroundings. There are no things that distract the reader, entertain, or provide any unclear narrations. Therefore, I communicate with them and consider them my friends.”

“If after the war we emerge as a modern state, where the value of every person is at its utmost, I will consider it an absolute victory for Ukraine.”

“If after the war we emerge as a modern state, where the value of every person is at its utmost, I will consider it an absolute victory for Ukraine.”

Like millions of Ukrainians, Olha is waiting for the war’s end. However, she does not make long-term plans.

“You know, there is nothing worse than self-deception. The point is that we don’t know, and it’s fair when there will be victory. And what this victory will look like is also important. From a military point of view, the victory for me is undoubtedly the return to the borders internationally recognized in 1991. But that’s not all. In order for Ukraine’s victory to be final and inevitable, the Russian Federation in its current form and format must cease to exist. I didn’t say that; it was said many years ago by the late Valeriya Novodvorska. Russia should break up into at least a dozen peaceful democratic nuclear-free states. And this will be salvation for everyone. And also: there are certain trends that are not very noticeable now, but I am afraid they will gain momentum. When we win, I don’t want Ukraine to become an analog of Russia internally and mentally. I’ll explain what that means. The attitude to democratic values, the attitude to the value of life, and the importance of every opinion. But the war dictates a different agenda; we must be tough and unequivocal. If we want to be part of the European community, peacetime will require Ukraine to confirm that we were, are, and remain the embodiment of the best European human values. If this happens, if after the war we emerge as a modern state where the value of every person will have weight, I will consider it an absolute victory for Ukraine,” concluded journalist Olha Musafirova.

JOURNALISTS ARE IMPORTANT. Stories Of Life And Work In War Conditions is a series of materials prepared by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU) team with the support of the Swedish human rights organization Civil Rights Defenders.

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post