The President of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU), Sergiy Tomilenko, told Andrii Kulikov on Hromadske Radio about the frontline press, russian propaganda in the occupied territories, and the Ukrainian experience that is taking over the world.

Five kilometers from russian positions in Huliaipole, three kilometers from the border in Velyka Pysarivka, under constant fire in Orikhiv, people do not get their news from a telethon or major channels. Their only source of verified information is a local newspaper, which volunteers deliver on bicycles, because postal operators refuse to go there because of the danger, and cars become easy targets for russian drones.

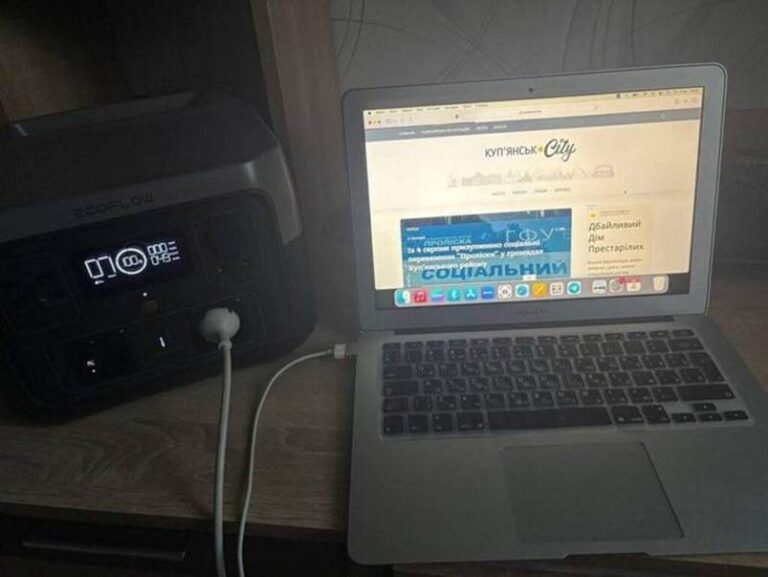

When the electricity goes out, paper remains.

With the support of the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the NUJU conducted a study of the information needs of residents of frontline territories. The biggest demand is not for general information about the war, but for the most localized security information: are shelters ready in the village where the reader lives, are there anti-drone nets, and where to evacuate from here?

Sergiy Tomilenko drew attention to a peculiar paradox of media consumption: social networks (Telegram, Viber) remain the most accessible source of news, used by about 90% of the population. But trust in them is low due to “information noise”. In contrast, trust in professional media – online publications and printed press – is two to three times higher…

The NUJU helped revive more than 35 frontline newspapers in different regions. Their names, which are Obrii Iziumshchyny, Holos Huliaipillia, Zmiyivskyi Kurier, Vorskla, Novyi Den, and Ridnyi Krai, sound like a poetic geography of resistance.

Sergiy Tomilenko explains: the russian war has actually thrown Ukrainians back in time a hundred years. Where russia is destroying infrastructure, where there is no guaranteed access to electricity and communications, it is printed newspapers that become a vital channel of information, not about global events, but about what is happening within a radius of 15-20 kilometers: where to evacuate, how to receive payments, whether the shelter in the neighboring village is working.

This year, the Canadian publication The Globe and Mail prepared a report from Velyka Pysarivka in the Sumy Region. This was not an article about the dangers of living near the border in general, but about the importance of a local newspaper. Journalist Mark MacKinnon’s conclusion: such newspapers give hope that people are not alone.

The regularity of the frontline press is from once a week to once a month, depending on the security situation. Journalists deliver newspapers themselves in their own cars or provide them through volunteers. Kateryna Zavarzina from Novomykolayivka, Zaporizhzhia Region, said, “If a year ago it was possible to come by car and bring 300 copies, now, due to increased drone attacks, we have to rely on volunteers with bicycles.”

Working under enemy drones and missiles

Sergiy Tomilenko emphasizes the radical change in the concept of “frontline zone.” Previously, this meant 2-5 kilometers to the contact line. Now, due to the drone danger, it is 25-30 kilometers. This fall, three journalists were killed by russian drones, including French reporter Antoni Lallikan (near Druzhkivka) and two Ukrainian journalists from the Freedom TV channel, Alena Hramova (Hubanova) and Yevhen Karmazin, in Kramatorsk.

The NUJU began advising last year to remove the PRESS branding from bulletproof vests – it had become a target for the russians, not a means of protection.

In the temporarily occupied Zaporizhzhia Region, after a full-scale invasion, the occupiers opened four local propaganda FM stations. Their waves reach the Ukrainian Nikopol on the opposite bank of the Dnieper River. Two years ago, the russians targeted the newsroom of the local radio station Nostalgie. This small independent broadcaster had become an alternative to the four occupying radio waves. The NUJU helped revive the station, but now all employees work exclusively from home. Only one person comes to the office once a day, edits the next 24 hours of broadcasts, and connects them to a charging station provided by Scandinavian partners.

Solidarity Centers and the Frontline Stories Bureau

After the start of the full-scale invasion, the NUJU deployed a network of Journalists’ Solidarity Center (JSC), which are regional hubs equipped with computers, Starlink, bulletproof vests, and helmets. Three frontline centers are operating as a priority: in Kharkiv, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro. Other centers are located in Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Lviv (with a presence in Chernivtsi).

The Ukrainian experience became the flagship initiative of UNESCO Safe Places for Journalists. Three media centers were created under the Ukrainian protocol in the Gaza Strip. The President of the Palestinian Association of Journalists, Nasser Abu Bakr, a laureate of the UNESCO Prize, admitted on World Press Freedom Day in Brussels that it was the Ukrainian model that was recommended as a basis.

Next year, under the auspices of the European Federation of Journalists, a joint presentation of the experience of Ukrainian and Palestinian centers is planned at the European Festival of Journalism.

Assistance to the Ukrainian media sphere is also urgently needed because it has been hit very hard by the economic crisis. For example, Odesa, the former capital of regional broadcasting with dozens of TV channels, today does not have a single TV channel of its own. Television is a costly business that cannot survive without advertising and grants.

On the other hand, Sergiy Tomilenko speaks of an alarming trend: the danger to journalists is growing, and international aid is winding down. Organizations are switching to other conflicts – Gaza, Latin America, Sudan. The sudden stop of USAID hit not only Ukrainian editorial offices that received aid, but also global human rights organizations that relied on American funding.

In these conditions, the NUJU hopes for constant contact with European partners. This summer, not yet knowing about the terrible shelling in the fall, they managed to transfer 50 charging stations to regional editorial offices – now they are critically important for the information pipeline.

There are other positive examples. The Swedish Media Business Association has allocated funds for a six-month program of direct financial support for frontline newspapers. The union announced a public competition and received 55 applications, from which it selected 25.

But this is not just humanitarian aid. Together with Swedish colleagues, the NUJU is creating the Frontline Press Bureau, a team of Kyiv journalists who will work with each editorial office, helping to prepare materials for Western media. There are agreements with leading publications in Denmark and Norway. The goal is to show the human stories of ordinary Ukrainians who, in these difficult times, find the strength to help others or survive these events, preserving their dignity.

One of the ways to overcome the crisis in media financing is their digital transformation. Paradoxically, it is the frontline media that have become the leaders of the transformation. Receiving training assistance and donor funding, they are more likely to switch to multi-platform.

The most striking example is the Chernihiv-based Visnyk Chernihivshchyny, the most widely circulated regional newspaper in Ukraine, with a circulation of 25,000 copies. Editor-in-chief Serhii Nadorenko resisted online for a long time, but after training, he introduced monetization of Facebook (the first USD 800), TikTok (some videos gain 2.5 million views), and YouTube. Each of the eight journalists must submit at least two videos a week.

History in a binder

An editor from Novomykolayivka, Zaporizhzhia Region, says: The first thing journalists think about under the pressure of the current circumstances is how to take the newspaper binder to a safe place because this is the history of the local community, the history of the war, which future generations will study.

Sergiy Tomilenko sums up: a local newspaper is local history. When it’s all over, researchers will study the war and Ukraine precisely from the pages of local newspapers. Where big media talk about global trends, local press records how a specific community, specific people experienced every day of a full-scale invasion.

And as long as there are journalists ready to deliver newspapers on bicycles under drones, as long as readers are waiting for their “District newspaper” as a connection to the world, there is hope. Pages of Hope, as the documentary about the Orikhiv newspaper was called.

NUJU Information Service

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

THE NATIONAL UNION OF

JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

Discussion about this post